Every year, counterfeit drugs kill more children than malaria alone. In rural clinics across Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, people are dying not because they lack access to medicine-but because the medicine they’re given is fake. These aren’t just poor-quality pills. They’re dangerous imposters: some have no active ingredient at all. Others contain toxic chemicals. A few even have the wrong dose-too little to work, too much to be safe.

What Exactly Are Counterfeit Drugs?

Not all bad medicine is the same. The World Health Organization draws a clear line between substandard and falsified medicines. Substandard drugs are real products that failed quality checks-maybe they expired, were stored wrong, or were made with bad ingredients. Falsified drugs are outright frauds. They’re made to look real but aren’t. The packaging, the logo, the color, the shape-they copy the real thing with 90% accuracy. Even trained pharmacists can’t tell the difference without tools.

In developing nations, up to 30% of medicines in some areas are falsified. In parts of Southeast Asia, half the antimalarial drugs on the market are fake. In West Africa, counterfeit antibiotics are so common that doctors now assume a pill won’t work unless it’s verified. These aren’t rare cases. They’re the norm.

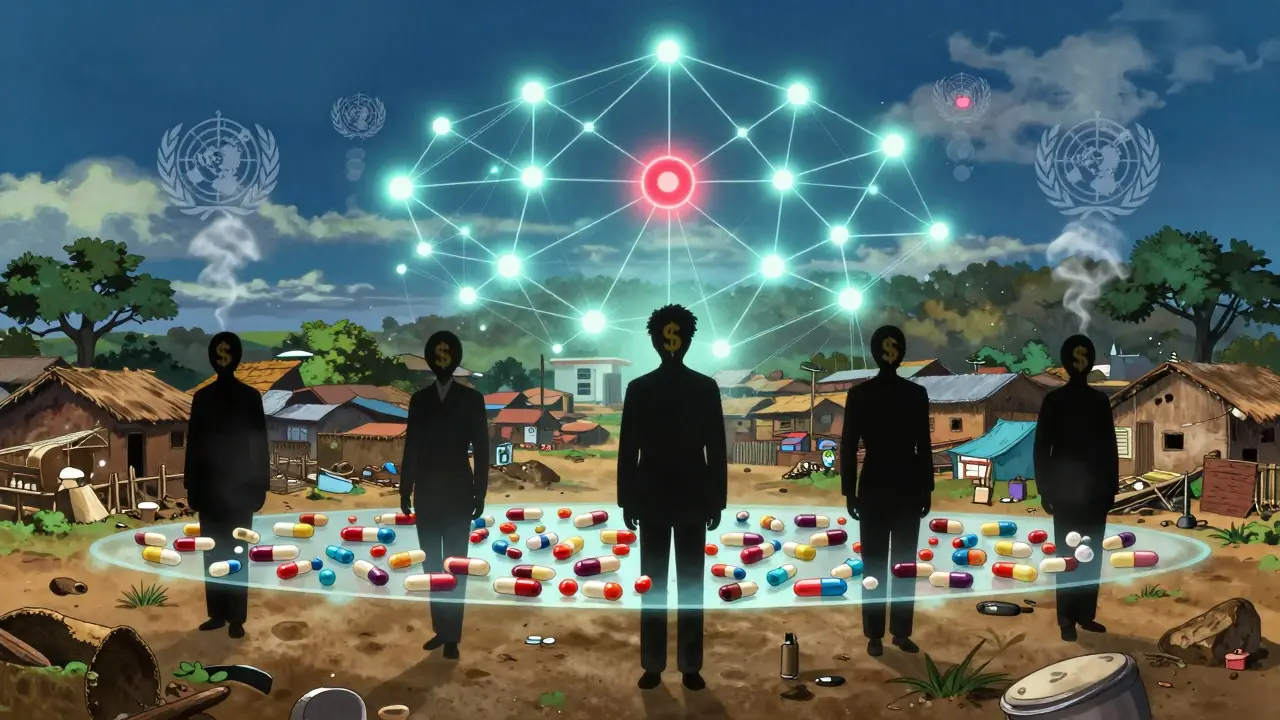

Why Are Fake Drugs So Common in Poor Countries?

It’s not just about corruption. It’s about desperation. A real course of malaria treatment can cost $5 to $10 in a low-income country. A fake version? $0.25. For families living on $2 a day, the choice isn’t between good and bad medicine-it’s between medicine and nothing. And the criminals know it.

Counterfeiters make up to 9,000% profit on these drugs. That’s more than smuggling weapons or drugs. And the risk? Almost none. In many countries, selling fake medicine carries a fine of a few hundred dollars-or no penalty at all. Meanwhile, the health systems are too weak to monitor supply chains. A single fake batch can pass through five or seven middlemen before reaching a village pharmacy. No one checks it. No one can.

How Do These Fake Drugs Kill?

It’s not dramatic. No explosions. No screaming. Just slow, silent death.

Take antibiotics. A 2022 Lancet study found that 87% of counterfeit antibiotics in developing nations had too little active ingredient to kill bacteria. That doesn’t just mean the patient doesn’t get better. It means the infection lingers. The bacteria adapt. And soon, the real antibiotics stop working too. This is how drug-resistant superbugs spread. The WHO warns that counterfeit medicines are now a major driver of antimicrobial resistance-something that could make simple infections deadly again.

For malaria, the numbers are worse. In sub-Saharan Africa, over 116,000 deaths each year are linked to fake antimalarials. Children are the most vulnerable. The OECD estimates that falsified drugs contribute to 72,000-169,000 child pneumonia deaths annually. In 2012, over 200 people in Lahore, Pakistan died after being given heart medication contaminated with a toxic chemical. The drugs had been distributed through public hospitals. No one tested them.

And it’s not just infections. Fake cancer drugs, diabetes pills, epilepsy treatments-they’re all out there. In 2022, patients across multiple countries received counterfeit cancer drugs that contained nothing but sugar and chalk. Their tumors kept growing. Their families were left wondering why treatment failed.

How Do You Spot a Fake Drug?

You can’t. Not reliably.

Visual inspection-the kind most people and even some pharmacists rely on-is only 30% effective. The packaging looks right. The blister packs feel right. The pills have the right imprint. But inside? Nothing. Or worse.

Some counterfeiters now use 3D printing to replicate packaging with 99% accuracy. They copy holograms, UV markings, even batch numbers. One Nigerian mother told a WHO interviewer: “I checked the seal. I looked at the expiration date. I asked the pharmacist. He said it was real. My son died two days later.”

There are tools. Spectroscopy machines can detect fake drugs with 95% accuracy. But they cost $20,000-and require trained technicians. In 85% of rural clinics in low-income countries, they don’t exist. Chemical test kits cost $5-$10 per test and are 70% accurate. But most clinics can’t afford them, or don’t have electricity to run them.

What’s Being Done to Stop It?

Some solutions are working.

In Ghana, the mPedigree system lets people text a code from the medicine package to a free number. Within seconds, they get a reply: “Real” or “Fake.” It’s simple. It works. Over 15,000 people have used it. One user wrote: “The SMS verification saved my child’s life.”

Pfizer has blocked over 302 million counterfeit doses since 2004 using blockchain tracking. The WHO launched its Global Digital Health Verification Platform in March 2025, using blockchain to trace drugs from factory to patient. It’s already live in 27 countries.

But here’s the problem: only 22% of pharmacies in low-income countries use any verification system. In high-income countries? 98%. The gap isn’t just technical-it’s economic. Solar-powered verification devices have been deployed in 12 African countries with 85% uptime. But they need training. And in 75% of rural clinics, staff can’t read or use smartphones without help.

Community health workers are making a difference. In pilot programs, training local volunteers to check medicine packages and report fakes reduced counterfeit use by 37%. Simple. Low-tech. Effective.

Why Isn’t More Being Done?

Because it’s not just a health issue. It’s a political one.

Only 45 of the 76 countries that signed the Medicrime Convention have made it national law. Border checks are weak. Customs officials are underpaid. Police don’t prioritize fake medicine cases. And the companies that make real drugs? They’re focused on profits, not enforcement. The $83 billion counterfeit market is growing faster than the legitimate one-12.3% a year versus 5.7%.

Meanwhile, the cost of fake drugs drains billions from health budgets. The WHO says countries spend $30.5 billion a year on fake or substandard medicines. That’s money that could build clinics, hire nurses, or train doctors.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, says it best: “Substandard and falsified medical products are a symptom of weak health systems-and a cause of their further weakening.”

What Can You Do?

If you live in a developing nation:

- Use verification apps like mPedigree or the WHO’s new platform if they’re available.

- Ask for the batch number and check it on a phone-even if you need help.

- Report suspicious medicines to local health authorities. Silence kills.

- Don’t buy medicines from street vendors or unlicensed online sellers.

- Know that if the price seems too good to be true, it is.

If you’re in a position to help-whether as a donor, policymaker, or global citizen:

- Support programs that train community health workers.

- Push for stronger laws and enforcement against counterfeiters.

- Advocate for affordable, reliable medicines to be available everywhere-not just in rich countries.

- Donate to organizations that supply verification tools to rural clinics.

The fight against fake drugs isn’t about catching criminals. It’s about fixing systems. It’s about making sure that when a mother buys medicine for her sick child, she isn’t buying a death sentence.

What’s Next?

The threat is growing. AI is now being used to generate fake packaging. Cryptocurrency makes payments untraceable. By 2027, the counterfeit drug market could hit $120 billion.

But there’s hope. The EU is pledging €250 million to strengthen supply chains in 30 developing nations by 2026. The WHO aims to cut counterfeit drug rates below 5% by 2027. If we scale up what’s already working-simple tech, trained locals, strong laws-we can win.

It won’t be easy. But every life saved starts with one verified pill.