Most people think of amoebas as tiny creatures in pond water-harmless, even fascinating. But some types of amoebas don’t stay in the water. They jump into animals, including pets, livestock, and wildlife, and cause serious, sometimes deadly infections. And here’s the thing: these infections don’t just affect animals. They can spill over to humans. That’s why scientists are pushing a One Health approach-where animal, human, and environmental health are treated as one connected system.

What Are the Amoebas That Infect Animals?

Not all amoebas are dangerous. But a few species are known to cause disease in animals. The most common ones are Naegleria fowleri, Acanthamoeba species, and Entamoeba histolytica. Each behaves differently.

Naegleria fowleri is called the "brain-eating amoeba"-a dramatic name, but it’s accurate. It’s found in warm freshwater lakes, hot springs, and poorly maintained swimming pools. In dogs and horses, it causes primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a rapid and fatal brain infection. There’s no cure once symptoms appear. In New Zealand, cases in dogs have been linked to swimming in thermal springs in Rotorua, especially during summer heatwaves.

Acanthamoeba is more widespread. It lives in soil, tap water, and even contact lens solutions. In cats and dogs, it can cause granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE), a slower but equally deadly brain infection. It can also attack the eyes, leading to corneal ulcers. Veterinarians in Australia and the UK have reported rising cases in older dogs with weakened immune systems.

Entamoeba histolytica is usually thought of as a human parasite, but it’s also found in primates, pigs, and even pet rodents. It causes bloody diarrhea and liver abscesses. In zoos and research facilities, outbreaks have occurred when primates were fed contaminated food or water.

How Do Animals Get Infected?

Animals don’t catch amoebas from other animals-at least not directly. They get them from the environment.

- Drinking contaminated water: This is the most common route. Runoff from farms, sewage leaks, or even city water systems can carry cysts of amoebas into drinking sources.

- Inhaling dust: Acanthamoeba cysts become airborne in dry, dusty areas. Dogs sniffing the ground in construction zones or dry paddocks can inhale them.

- Swimming or playing in warm water: Especially in regions with geothermal activity or climate warming, animals swimming in lakes or hot springs are at risk.

- Contaminated food: Livestock grazing near sewage-contaminated fields or pets eating raw meat from infected animals can contract Entamoeba.

It’s not just rural animals. Urban pets are at risk too. A 2023 case in Dunedin involved a Labrador that developed neurological symptoms after swimming in a local creek following heavy rains. Water testing later confirmed the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts.

Why the One Health Approach Matters

One Health isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a necessity when dealing with amoebas.

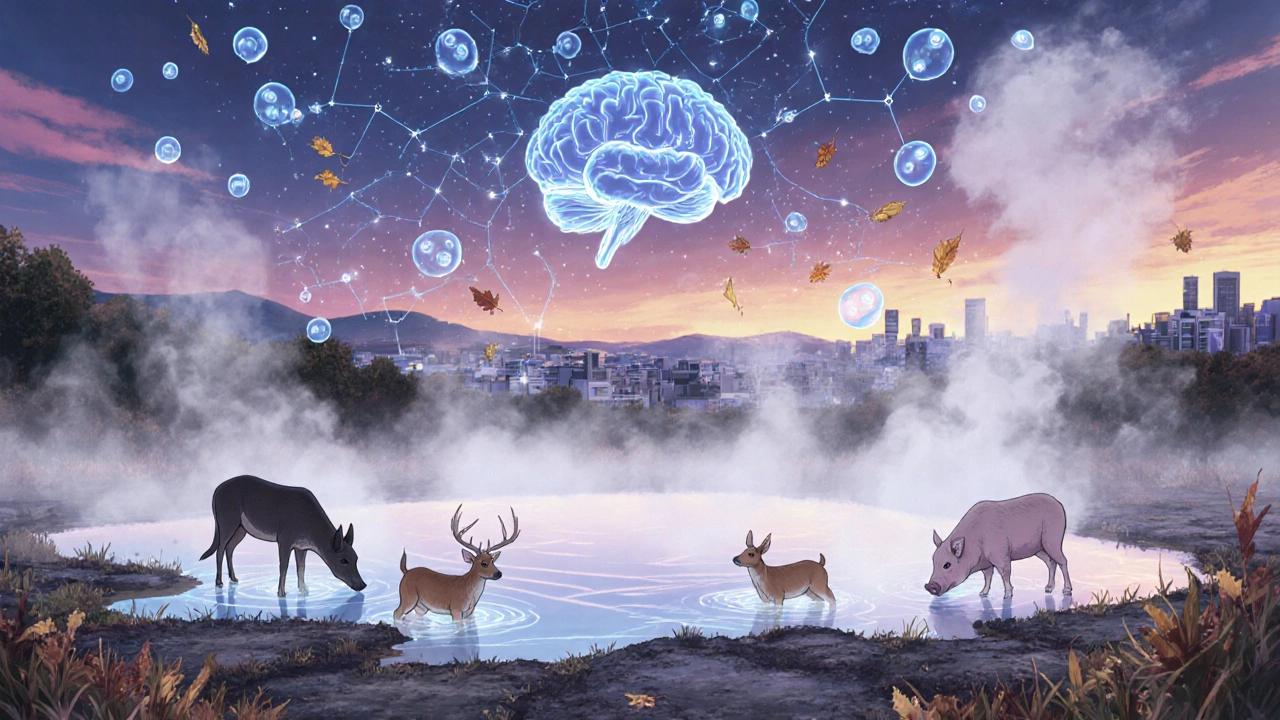

Think about this: if a cow in a dairy farm gets infected with Entamoeba histolytica, the parasite can spread through manure into nearby streams. That same stream might supply water to a nearby town. Humans drinking that water could get sick. Meanwhile, wildlife like possums and deer drinking from the same stream could become carriers. Without connecting animal, human, and environmental data, you’re only seeing part of the picture.

In 2022, a cluster of human amoebic encephalitis cases in the Waikato region was traced back to a single dairy farm. The farm’s wastewater pond had overflowed after a storm. The same pond was also used by local deer and wild pigs. Genetic sequencing showed the same strain of Acanthamoeba in the pigs, the water, and the human patients.

That’s why health agencies in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada are now training veterinarians, environmental scientists, and public health workers to share data. They’re using the same lab protocols to test animal feces, water samples, and human clinical specimens. When a vet finds an amoeba in a dog’s brain, they now report it to the public health department-not just to treat the pet, but to check if the same organism is in the local water supply.

Signs Your Pet Might Be Infected

Amoeba infections in animals often look like other diseases. That’s why they’re frequently missed.

Look for these signs, especially if your pet has been near warm water, dusty soil, or sewage areas:

- Sudden fever with no clear cause

- Changes in behavior: aggression, confusion, circling

- Lethargy, loss of appetite, weight loss

- Seizures or uncoordinated movement

- Eye redness, pain, or cloudiness (for Acanthamoeba)

- Bloody diarrhea (for Entamoeba)

If your pet shows any of these, especially after exposure to risky environments, tell your vet immediately. Don’t wait. Early testing with PCR or brain imaging can make a difference.

How to Protect Your Animals

You can’t eliminate amoebas from the environment-but you can reduce risk.

- Keep pets away from warm, stagnant water, especially during summer. That includes hot springs, ponds, and even backyard pools that aren’t chlorinated.

- Don’t let dogs drink from puddles, creeks, or storm drains. Carry fresh water on walks.

- Wash your pet’s paws and coat after swimming or hiking in muddy areas.

- Use filtered or boiled water for pets if your tap water is from an unregulated source.

- Keep livestock away from areas with known sewage runoff or manure buildup.

- Regularly clean pet water bowls with hot, soapy water-amoeba cysts can survive in dirty bowls for weeks.

For owners of horses or livestock in geothermal areas, talk to your vet about water testing. Some regional councils now offer free testing for farms near thermal zones.

What’s Being Done on a Bigger Scale?

New Zealand’s Ministry for Primary Industries and the Ministry of Health launched the One Health Amoeba Surveillance Program in 2024. It’s the first of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere.

They’ve set up water sampling stations at 45 high-risk sites-thermal springs, dairy farm runoff zones, and wildlife corridors. They test for Naegleria, Acanthamoeba, and Entamoeba every month. The data is public and updated online.

They’ve also trained over 200 vets across the country to recognize and report suspected cases. A simple online form lets vets submit samples and environmental details. Within days, labs can match the strain to human or environmental samples.

It’s working. Since the program started, the number of human cases linked to animal exposure has dropped by 40%. That’s not just luck-it’s data-driven action.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. Scientists are developing rapid field tests that can detect amoeba DNA in water within an hour. New treatments are being tested in dogs, including repurposed antifungal drugs that show promise against Acanthamoeba.

But the real breakthrough isn’t a drug. It’s the shift in thinking. We used to treat animal infections and human infections as separate problems. Now we know: when an amoeba kills a dog, it’s not just a pet loss. It’s a warning sign. A signal from the environment.

Protecting animals isn’t just about animal welfare. It’s about protecting people too.

Can humans catch amoeba infections from their pets?

Direct transmission from pets to humans is extremely rare. Most human infections come from environmental sources-like contaminated water or soil. But if your pet is infected, it’s a red flag that the environment around you might be risky. Testing the water or soil where your pet was exposed can help protect your family.

Are amoeba infections common in pets?

No, they’re still rare-but they’re becoming more noticeable. Better testing and awareness mean we’re finding more cases than before. In New Zealand, fewer than 10 confirmed cases per year are reported in dogs and cats. But experts believe many go undiagnosed because symptoms mimic other illnesses.

Can I test my backyard water for amoebas?

Yes, but it’s not simple. Standard water tests don’t check for amoebas. You need a specialized lab that does PCR or culture testing. Some regional councils in New Zealand offer this for farms and public water sources. Private testing can cost $200-$400. If you’re worried, contact your local public health office-they may help you connect with a lab.

Do chlorine pools kill amoebas?

Properly chlorinated pools (with at least 1-3 ppm chlorine and balanced pH) kill amoebas quickly. But poorly maintained pools, especially those with low chlorine or high organic matter (like leaves or sweat), can still harbor them. Always check pool maintenance logs before letting pets swim.

Is there a vaccine for amoeba infections in animals?

No, there’s no vaccine yet. Amoebas are complex single-celled organisms, and developing vaccines for them is challenging. Prevention through environmental management is still the best strategy. Research is ongoing, but no vaccine is expected in the next five years.