When you fill a prescription for a brand-name drug, you expect to get the cheapest option available-especially if a generic version has been approved and is legally allowed to be swapped in. But in many cases, that’s not what happens. Behind the scenes, big pharmaceutical companies are using legal loopholes and aggressive tactics to block generic drugs from reaching patients, even when state laws say they should be allowed. This isn’t just about profit-it’s about antitrust violations that cost consumers billions every year.

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

In the U.S., most states have laws that let pharmacists automatically substitute a generic drug for a brand-name version, as long as it’s bioequivalent-meaning it works the same way in the body. These laws exist to save money. Generics cost 80% to 90% less than brand-name drugs. When a patent expires, generics flood the market, and prices drop fast. In states with strong substitution laws, generics often capture 80-90% of the market within months. But here’s the catch: drugmakers don’t want that to happen. They’ve figured out how to game the system. Instead of waiting for generics to compete fairly, they change their product just before the patent runs out-and then pull the original version off the market. This is called product hopping or hard switching.Product Hopping: The Playbook

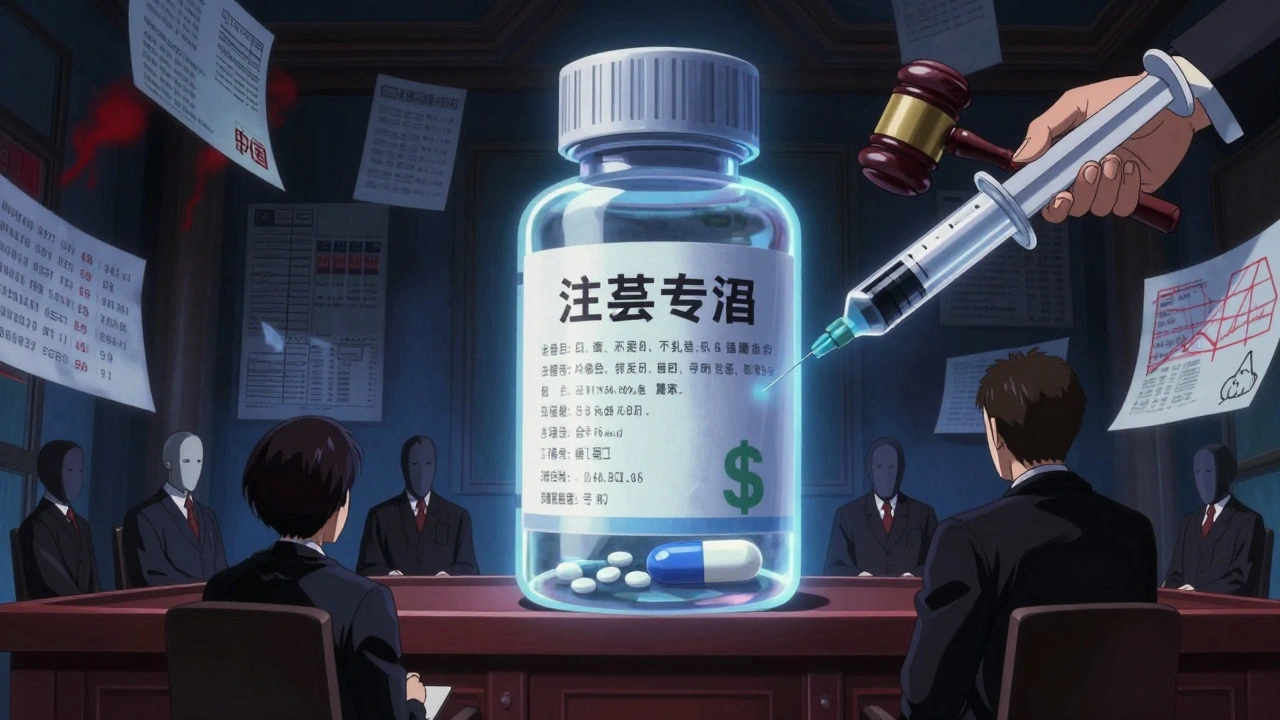

One of the most famous cases involved Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. The original version, Namenda IR (immediate release), was taken multiple times a day. When its patent was about to expire, the manufacturer, Actavis, introduced Namenda XR-a once-daily extended-release version. Then, 30 days before generics could legally enter the market, they pulled Namenda IR off shelves entirely. Why does this matter? Because pharmacists can’t substitute a generic for Namenda XR if the original Namenda IR is gone. The substitution laws only apply to the exact drug that was prescribed. So patients who were on Namenda IR were forced to switch to the new version, which was still under patent protection. Even if a generic version of Namenda IR became available, doctors couldn’t prescribe it because it was no longer on the market. Patients didn’t want to go back-switching back meant more pills, more visits, more hassle. The result? Generics were locked out. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2016 that this was illegal. They said Actavis didn’t just innovate-they manipulated the system to kill competition. This was a landmark decision. But it’s not the norm.Why Some Courts Let It Slide

Not all courts see product hopping the same way. In the Nexium case, AstraZeneca switched patients from Prilosec to Nexium-a slightly different version of the same drug. But they kept selling Prilosec. Because the original drug was still available, the court said this wasn’t anticompetitive. It was just offering a new product. That’s the loophole. If the original drug stays on the shelves, even if it’s barely used, courts often say the company did nothing wrong. But when the original is pulled, it’s a different story. The FTC’s 2022 report called this inconsistency dangerous. It lets companies pick and choose when to follow the rules. Take Suboxone, a drug for opioid addiction. Reckitt Benckiser replaced the tablet version with a film strip, then spread claims that the tablets were unsafe-claims later found to be false. They threatened to pull the tablets, knowing patients and doctors would panic and switch to the film. The FTC stepped in, saying this was coercion. In 2019 and 2020, Reckitt settled for millions and had to stop the practice.

The Hidden Weapon: REMS Abuse

Another tactic is even harder to spot. It involves something called REMS-Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. These are safety programs required by the FDA for certain drugs, especially those with serious side effects. But some brand-name companies use REMS to block generic makers from getting the samples they need to prove their drugs are equivalent. To get FDA approval, generics must test their drug against the brand-name version. But if the brand refuses to sell samples-or only sells them under impossible conditions-generics can’t enter the market. According to legal scholar Michael A. Carrier, over 100 generic companies have reported being blocked this way. One study found that for 40 drugs with restricted access, this tactic alone cost consumers more than $5 billion a year. It’s not just about samples. Some companies tie REMS to exclusive distribution deals, making it illegal for pharmacies to stock generics until the brand is sold out. This isn’t safety-it’s sabotage.Who Pays the Price?

The numbers don’t lie. The FTC estimates that delayed generic entry costs U.S. consumers and taxpayers billions each year. Just three drugs-Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid-cost an estimated $167 billion more in the U.S. than in Europe, where generics enter faster. Revlimid’s price jumped from $6,000 to $24,000 per month over 20 years. Copaxone, a multiple sclerosis drug, saw a $4.3 billion to $6.5 billion price spike over two and a half years after Teva introduced a new version and pulled the old one. In the Ovcon case, a birth control pill was replaced with a chewable version, and the original was pulled-so generics couldn’t be substituted. Market share for generics dropped from 80% to under 20%. These aren’t accidents. They’re calculated moves. The goal isn’t to improve care-it’s to extend monopoly pricing as long as possible.