Why Low Blood Sugar Is a Silent Threat for Seniors with Diabetes

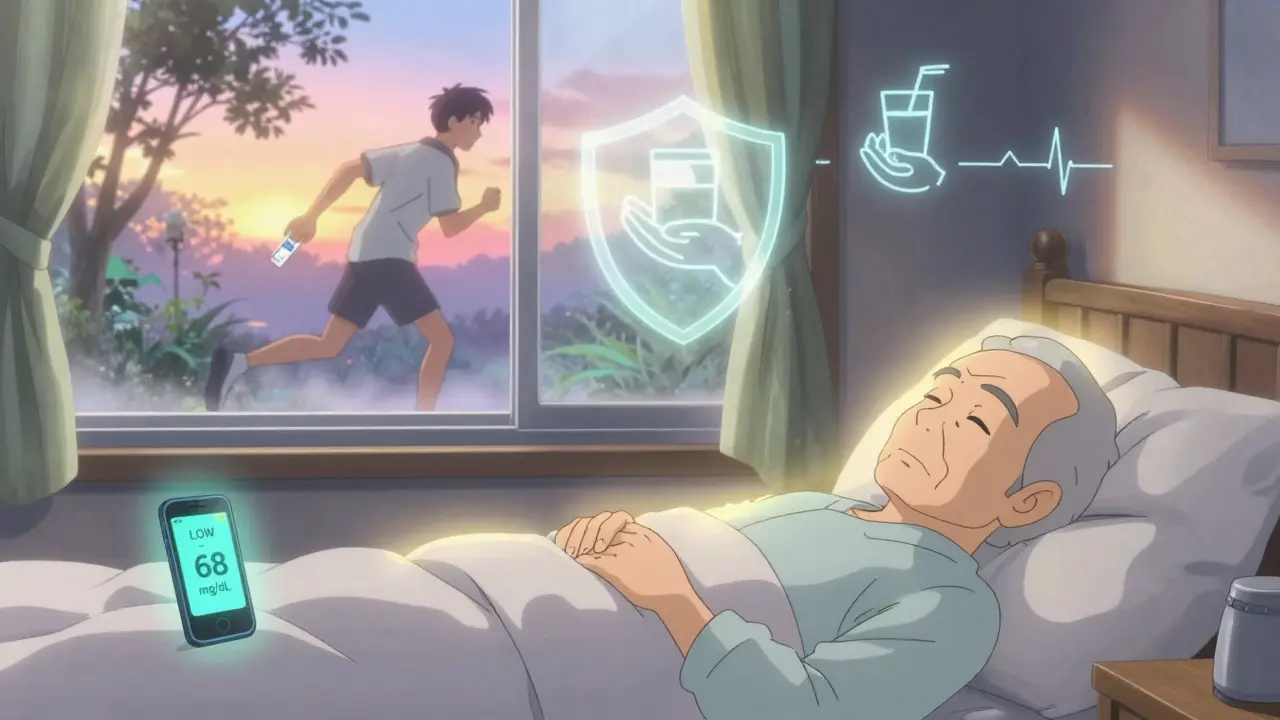

For older adults with diabetes, the biggest danger isn’t high blood sugar-it’s low blood sugar. A blood glucose level below 70 mg/dL might seem minor, but in someone over 65, it can lead to a fall, a trip to the ER, or even a heart attack. Seniors are two to three times more likely than younger people to have dangerous hypoglycemic episodes. Why? Their bodies don’t respond the same way. Kidneys slow down, hormones that warn of low sugar don’t kick in as quickly, and many are taking multiple medications that interact in unpredictable ways.

One study found that after just one severe low blood sugar episode, the chance of dying within a year jumps by 60%. That’s not a small risk. It’s life-altering. And it’s often preventable-not by chasing lower A1C numbers, but by choosing the right medications and avoiding the ones that put seniors in danger.

Medications That Put Seniors at Highest Risk

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to safety in older adults. Some are fine. Others are ticking time bombs.

The worst offender? Glyburide. This sulfonylurea, sold under names like Glynase and Micronase, stays in the body too long, especially in seniors with reduced kidney function. It doesn’t care if you haven’t eaten or if you’re feeling dizzy-it keeps pushing insulin out, dragging blood sugar down. Studies show nearly 40% of elderly patients on glyburide have at least one hypoglycemic episode per year. In one case, an 82-year-old man fell three times in six months because of nighttime lows from glyburide. After switching meds, he hadn’t had a single episode in over a year.

Glyburide is so risky that the American Geriatrics Society explicitly lists it as a medication seniors should avoid. The Beers Criteria, used by doctors nationwide to flag unsafe prescriptions, calls it a "potentially inappropriate medication" for older adults. Even glipizide, another sulfonylurea, carries higher risk than newer options-though it’s slightly better than glyburide because it clears faster from the body.

Insulin also raises the risk. It’s powerful, yes-but in seniors, it increases fall risk by 30% because of dizziness and confusion from low sugar. Many seniors don’t realize they’re going low until it’s too late. Their warning signs-shaking, sweating, fast heartbeat-are muted. They just feel tired. Or confused. Or off. And then they stumble.

The Safer Alternatives: What Doctors Should Be Prescribing

There are better choices. Medications that lower blood sugar without crashing it.

DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin (Januvia), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and saxagliptin (Onglyza) are among the safest. These drugs work by helping the body use its own insulin more efficiently-only when blood sugar is high. They rarely cause hypoglycemia on their own. In clinical trials, only 2-5% of seniors on these medications had low blood sugar episodes, compared to 15-40% on sulfonylureas. One Reddit user shared that after switching his 82-year-old father from glipizide to linagliptin, his blood sugars stabilized between 90 and 140 without any scary drops.

SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) also have very low hypoglycemia risk. They work by making the kidneys flush out extra sugar through urine. When used alone, they cause hypoglycemia in only about 4.5% of users-far less than older drugs. They also help with heart and kidney protection, which matters a lot for seniors with other health issues.

Metformin is still the go-to first-line drug for many, but it’s not for everyone. It’s safe if kidneys are working well. But if creatinine clearance drops below 30 mL/min (common in people over 80), it’s risky. Doctors need to check kidney function regularly-not just once a year, but every 3-6 months.

And then there’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a newer injectable approved in 2022. In elderly trial participants, it caused hypoglycemia in just 1.8% of cases-compared to 12.4% with insulin. It’s not yet widely used in seniors, but it’s a sign of where the future is headed: drugs that don’t just control sugar, but don’t endanger lives doing it.

What Seniors and Caregivers Should Watch For

Even the safest medications can cause problems if you’re not paying attention. Hypoglycemia doesn’t always look like textbook shaking and sweating. In seniors, it often looks like:

- Confusion or disorientation

- Sudden drowsiness or weakness

- Headaches

- Irritability or unusual behavior

- Difficulty walking or balancing

- Fast heartbeat (though this can be masked by beta-blockers)

Many seniors don’t recognize these signs as low blood sugar. They think they’re just getting older. Or having a bad day. That’s why education is critical. Caregivers should know the symptoms and always have fast-acting sugar on hand-glucose tablets, juice, or even candy. If someone is confused and can’t swallow, don’t give them food or drink. Call 911. A glucagon kit should be in every home where a senior takes insulin or sulfonylureas.

How Often Should Medications Be Reviewed?

Diabetes treatment isn’t set-and-forget. It needs constant checking.

The American Diabetes Association recommends a full medication review every 3 to 6 months for seniors. That means looking at every pill, patch, and injection. Is that old glyburide prescription still necessary? Are there new drugs that could replace it? Are there other medications-like beta-blockers for high blood pressure or NSAIDs for arthritis-that make hypoglycemia worse?

Drug interactions are a hidden danger. Beta-blockers hide the warning signs of low sugar. NSAIDs like ibuprofen can boost the effect of sulfonylureas. Even some antibiotics and antifungals can cause dangerous drops. A pharmacist can spot these risks better than most doctors. That’s why medication reconciliation-where a pharmacist reviews all meds with the patient-is one of the most effective ways to cut hypoglycemia events. Studies show it reduces hospital visits by 28%.

Tools like the STOPP/START criteria help doctors decide what to stop and what to start. One study showed using this method cut hypoglycemia-related hospital stays by 32%.

Technology Can Save Lives

Forget fingersticks. For seniors, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are game-changers.

CGMs track sugar levels all day and night. They alert the user-and often a family member-when blood sugar is dropping. One study found seniors using CGMs had 65% fewer hypoglycemic episodes than those relying on traditional testing. For someone living alone, that’s huge. It means fewer falls, fewer ambulance rides, and more independence.

Many CGMs now work with smartphones and smartwatches. They can send alerts to a child’s phone if Grandpa’s sugar drops while he’s napping. Some even have automatic alerts to emergency services. They’re not cheap, but for many seniors, the cost of one fall-hospital stay, rehab, lost mobility-far outweighs the device price.

The Real Goal: Safety Over Numbers

Doctors used to chase A1C numbers like trophies. Get it below 7%. Then 6.5%. But for seniors, that mindset kills.

The American Diabetes Association now says clearly: "Avoiding hypoglycemia is a higher priority than achieving near-normal glycemia." That’s a shift. It means if a senior’s A1C is 8.0% or even 8.5%, and they’re not having lows, that’s a win. It means choosing a drug that keeps them steady over one that pushes numbers lower at the cost of safety.

Functional health matters more than lab results. Can they walk without falling? Can they remember to eat? Do they live alone? Are they confused sometimes? These questions guide treatment-not a single number on a chart.

There’s no one-size-fits-all. But there is one rule that always applies: if a medication is causing lows, it’s the wrong medication-even if it’s "working" on paper.

What You Can Do Today

- Ask your doctor: "Is my current diabetes medication safe for someone my age?" If you’re on glyburide, ask if you can switch.

- Request a medication review with a pharmacist. Bring all your pills-prescription, over-the-counter, supplements.

- Get a CGM if you’re on insulin or sulfonylureas. Ask if your insurance covers it.

- Teach a family member the signs of low blood sugar. Make sure they know where your glucose tablets and glucagon kit are.

- Keep fast-acting sugar (juice, glucose gel, hard candy) in every room, in your purse, and in the car.

Diabetes doesn’t have to mean fear. With the right meds, the right checks, and the right support, seniors can live well-without the constant threat of a low blood sugar crash.

What diabetes medications should seniors avoid?

Seniors should avoid glyburide (Glynase, Micronase) due to its high risk of prolonged hypoglycemia. Other sulfonylureas like glipizide carry moderate risk and should be used cautiously. Insulin also increases fall risk and requires careful dosing. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists glyburide as a medication to avoid in older adults.

Are DPP-4 inhibitors safe for elderly patients?

Yes. DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin (Januvia), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and saxagliptin (Onglyza) are among the safest options for seniors. They rarely cause hypoglycemia when used alone, with studies showing low blood sugar rates of only 2-5%. They’re recommended by the American Diabetes Association as preferred alternatives to sulfonylureas in older adults.

Can metformin cause low blood sugar in seniors?

Metformin alone rarely causes hypoglycemia. But it’s cleared by the kidneys, so it can build up in seniors with reduced kidney function, increasing the risk of lactic acidosis. Doctors should check creatinine clearance regularly and avoid metformin in patients over 80 or with eGFR below 30 mL/min.

How can continuous glucose monitors help seniors?

CGMs track blood sugar 24/7 and alert users when levels drop too low-even during sleep. Seniors using CGMs have been shown to have 65% fewer hypoglycemic episodes than those using fingersticks. They’re especially helpful for people living alone, those with cognitive decline, or those on high-risk medications.

What should I do if my elderly parent has a low blood sugar episode?

If they’re conscious and able to swallow, give them 15 grams of fast-acting sugar-4 ounces of juice, 3-4 glucose tablets, or 1 tablespoon of honey. Wait 15 minutes and check blood sugar again. If they’re confused, unconscious, or having a seizure, do not give them anything by mouth. Call 911 immediately and use a glucagon injection if available. Always keep glucagon on hand if they take insulin or sulfonylureas.