Diabetic retinopathy doesn’t come with pain, blurry vision, or warning signs-at least not at first. By the time you notice something’s wrong, it might already be too late. That’s why screening isn’t optional. It’s your best defense against losing sight to a condition that’s entirely preventable. Around 1 in 3 people with diabetes will develop some form of retinopathy. But here’s the good news: if caught early, diabetic retinopathy can be managed so effectively that 98% of severe vision loss can be avoided. The key? Knowing when to get checked and what happens next.

When Should You Get Screened?

Screening intervals aren’t one-size-fits-all. A person with well-controlled type 2 diabetes and no signs of eye damage can safely wait 2 to 4 years between checks. But someone with type 1 diabetes, poor blood sugar control, or early signs of retinopathy needs to be seen much sooner.

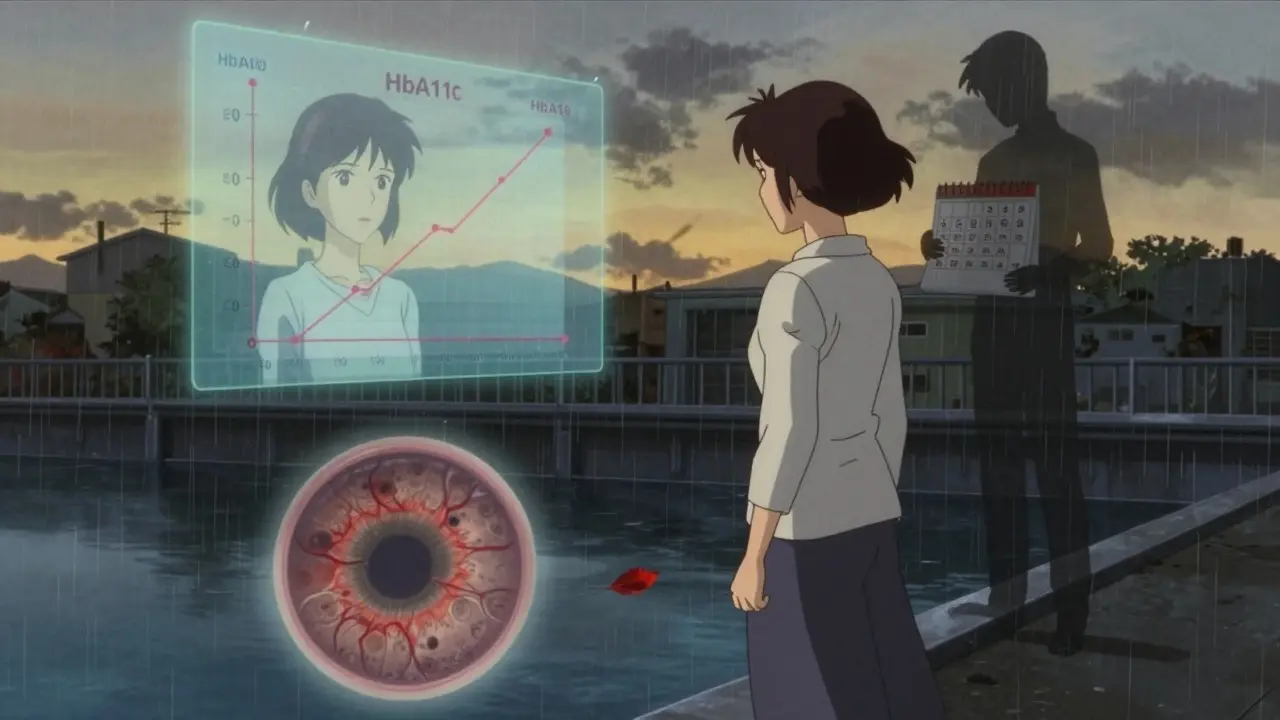

For type 1 diabetes, the first eye exam should happen 3 to 5 years after diagnosis. For type 2 diabetes, it’s right after diagnosis-because many people have had undiagnosed high blood sugar for years before they’re told they have diabetes. If the first screening shows no retinopathy and your HbA1c is below 7%, your next check can be in 1 to 2 years. If you’ve had two clean screenings in a row, you might be able to stretch it to every 2 to 3 years, especially if your blood pressure and kidney function are normal.

But if your HbA1c is above 8%, your blood pressure is over 140/90, or you have protein in your urine (a sign of kidney damage), you’re at higher risk. That means annual screenings, no exceptions. Pregnant women with diabetes need an exam in the first trimester and possibly again in the third, because pregnancy can speed up retinopathy progression.

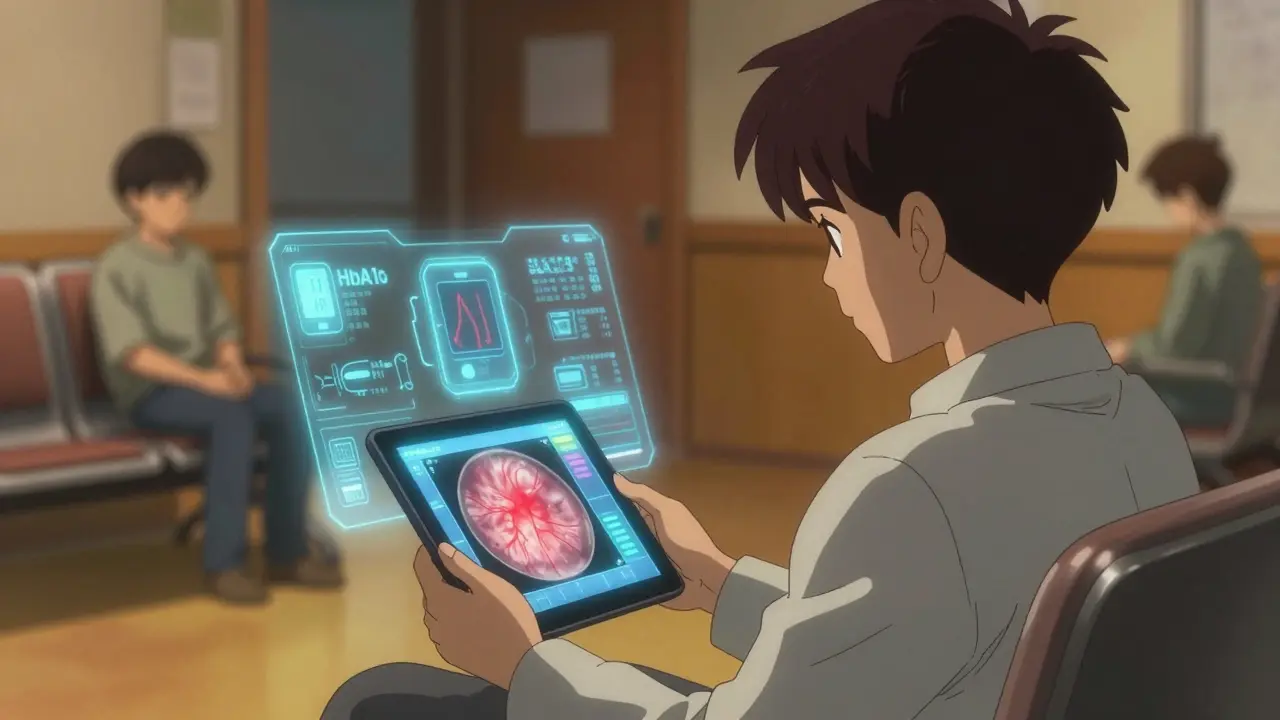

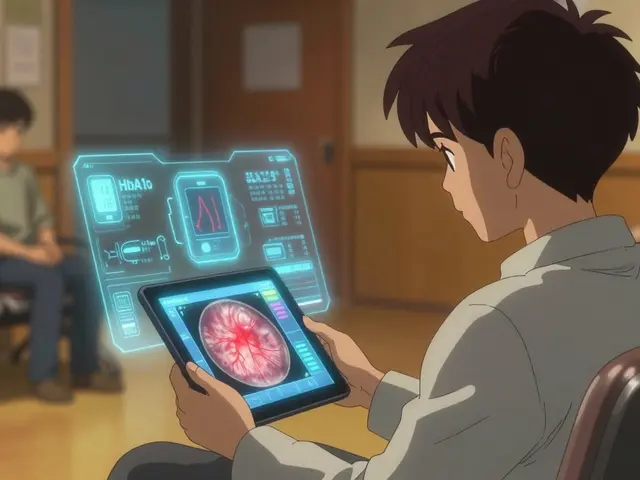

There’s a tool called RetinaRisk that uses your age, diabetes duration, HbA1c, blood pressure, and kidney function to calculate your personal risk. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than guessing. Some clinics use it. Others still rely on fixed schedules. Ask your doctor: Is my screening interval based on my actual risk, or just the default?

What Happens During a Screening?

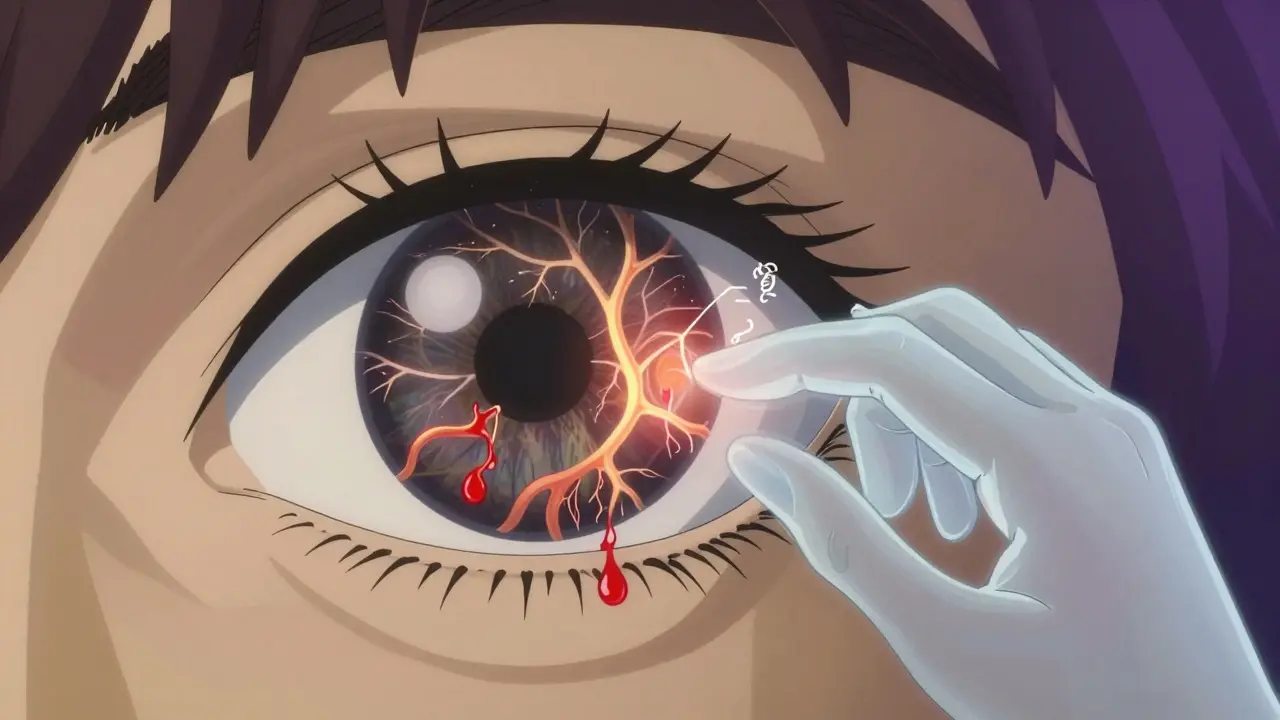

A diabetic eye screening isn’t just a quick glance. It’s a detailed image capture. Most screenings now use digital fundus photography-no bright light shined directly into your eye for minutes. Instead, a camera takes two or more photos of each retina, usually after your pupils are dilated. This gives a clear view of the blood vessels, swelling, and any abnormal growths.

The images are graded using the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Scale. It breaks things down into five levels:

- No apparent retinopathy

- Mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR)

- Moderate NPDR

- Severe NPDR

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)

Diabetic macular edema (DME)-fluid buildup in the central part of the retina-isn’t a separate stage but a complication that can happen at any level. It’s the most common cause of vision loss in people with diabetes.

Some clinics now use AI-powered tools to analyze images. Google’s DeepMind algorithm, for example, detects sight-threatening retinopathy with over 94% accuracy. In rural areas where ophthalmologists are scarce, telemedicine screening-where photos are sent to specialists remotely-is becoming the norm. One study found it caught 94% of cases that an eye doctor would have flagged.

What Happens If Retinopathy Is Found?

Not every case needs treatment. Mild NPDR? You’ll likely be monitored. But if it’s moderate or worse, you’ll be referred to an eye specialist. The goal isn’t to cure retinopathy-it’s to stop it from getting worse.

For moderate to severe NPDR, or any case of PDR, laser treatment (panretinal photocoagulation) is often the first step. It doesn’t restore vision, but it shrinks abnormal blood vessels and reduces the risk of bleeding or retinal detachment by over 50%. It’s done in the doctor’s office, usually with local anesthetic drops. You might see spots or glare afterward, but most people adapt quickly.

If you have diabetic macular edema, injections into the eye are the standard. Medications like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), or bevacizumab (Avastin) block VEGF-a protein that causes leaky blood vessels. You’ll need multiple injections, usually every 4 to 8 weeks at first, then spaced out as your eye stabilizes. Many patients see noticeable improvement in vision within months.

For advanced cases with bleeding or scar tissue pulling on the retina, a vitrectomy might be needed. This is surgery to remove the vitreous gel and any blood or scar tissue. Recovery takes weeks, but it can save vision when other treatments fail.

Can You Prevent It?

Treatment helps, but prevention is even better. The DCCT and EDIC studies showed that keeping HbA1c below 7% reduces the risk of developing retinopathy by 76% in type 1 diabetes. For type 2, tight control slows progression by more than half. Blood pressure control matters too-keeping it under 140/90 reduces retinopathy risk by 34%.

It’s not just about numbers. Consistency matters. Fluctuating HbA1c-jumping from 6.5% to 9% and back-is more damaging than staying at 7.5%. That’s why daily habits count: regular meals, movement, sleep, and stress management aren’t just general advice-they’re eye-saving actions.

Some people think once they’re on medication, they don’t need to change their lifestyle. That’s a myth. Medication helps, but it doesn’t replace healthy habits. A 2023 study found that people who combined good blood sugar control with regular exercise reduced their risk of vision-threatening retinopathy by 62% compared to those who only took pills.

What’s Changing in 2026?

Screening is getting smarter. AI tools are now FDA-cleared and widely used in the U.S., UK, and parts of Europe. New handheld devices like the D-Eye smartphone adapter let primary care providers take retinal images during routine visits-no need to wait for an eye specialist. This is huge for people in remote areas or those without easy access to clinics.

Screening intervals are shifting too. The old rule-“annual check for everyone”-is fading. Risk-based scheduling is now the standard in leading health systems. The UK’s national program switched to biennial screening for low-risk patients and saw no increase in vision loss. In fact, they saved over 200,000 unnecessary appointments in three years.

But disparities remain. In the U.S., only 58-65% of people with diabetes get screened yearly. In low-income communities, that number drops below 40%. The same gap exists in New Zealand and Australia. Technology alone won’t fix this. You need outreach, education, and systems that make screening easy, not another thing to manage.

What Should You Do Right Now?

Here’s your action plan:

- If you have diabetes and haven’t had an eye exam in the last year, schedule one now.

- Ask your doctor: What’s my risk level for retinopathy? Don’t accept “annual check” as the default.

- Get your HbA1c, blood pressure, and kidney function checked regularly. These numbers determine your screening frequency.

- If you’re pregnant or planning to be, talk to your doctor about eye screening before or during pregnancy.

- Don’t wait for symptoms. By the time your vision blurs, damage may already be done.

It’s not about fear. It’s about control. You manage your diabetes every day with food, meds, and activity. Your eyes deserve the same attention. One screening every year-or every two, if you’re low risk-isn’t a burden. It’s your insurance against losing the ability to see your family, your favorite places, your future.

What If I Miss My Screening?

If you’ve skipped a screening because it was “too much hassle” or “I feel fine,” you’re not alone. But here’s what you need to know: diabetic retinopathy doesn’t care how you feel. It grows silently. A 2022 study found that 31% of people who missed their annual screening developed sight-threatening retinopathy within 18 months.

Don’t wait for a warning sign. If you’ve missed your last check-up, book the next one today. Even if you’ve had two clean screenings, if your HbA1c has climbed above 8% recently, you’re no longer low risk. Your interval needs to change.

Can AI Replace the Eye Doctor?

AI doesn’t replace the eye doctor-it empowers them. Algorithms can scan thousands of images quickly and flag the ones that need attention. But they can’t diagnose complications like glaucoma or cataracts. They can’t assess your overall health or adjust your treatment plan. The best outcome happens when AI spots the problem, and a human decides what to do next.

Think of AI as a first filter. It’s like a smoke alarm: it doesn’t put out the fire, but it tells you when to call the firefighters.

What Are the Costs?

In the U.S., a diabetic eye screening without insurance can cost $100-$250. But most insurance plans, including Medicare, cover it fully under preventive care. In New Zealand, it’s free through the public health system if you’re enrolled in diabetes care. The UK’s national screening program is also free. If you’re worried about cost, ask your clinic: Is this covered under my plan? Most of the time, it is.

The real cost isn’t the price of the test. It’s the cost of vision loss-lost independence, lost jobs, lost quality of life. That’s why screening is one of the most cost-effective interventions in all of medicine.

How Do I Stay on Track?

Set a calendar reminder. Don’t rely on memory. Link your eye check-up to another annual health task-like your flu shot or dental cleaning. Make it a habit.

Keep a simple log: date of last screening, HbA1c result, blood pressure, and whether you were referred for treatment. Share it with your endocrinologist or GP. It helps them make better decisions.

And if you’re ever unsure-call your clinic. Ask for the screening protocol they follow. If they say, “We do it every year,” ask why. If they say, “We use risk-based scheduling,” ask what your risk level is. You have the right to know.

Can diabetic retinopathy be reversed?

Early stages of diabetic retinopathy, especially mild nonproliferative retinopathy, can stabilize or even improve with better blood sugar and blood pressure control. However, once damage like scarring, bleeding, or macular edema occurs, it cannot be fully reversed. Treatment can prevent further vision loss and sometimes improve vision, but lost retinal tissue doesn’t regenerate.

Do I need to get screened if I have type 2 diabetes but no symptoms?

Yes. Diabetic retinopathy often has no symptoms in the early stages. Many people don’t notice vision changes until the disease is advanced. Screening is the only way to detect it before it causes damage. The American Diabetes Association recommends an eye exam at diagnosis for type 2 diabetes, even if you feel fine.

How often should I get screened if I have mild retinopathy?

If you have mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, you should be seen by an eye specialist every 6 to 12 months. If your condition is stable and your blood sugar and blood pressure are well-controlled, your doctor might extend the interval to 12-18 months. But if your HbA1c rises or you develop swelling in the macula, you’ll need more frequent checks.

Is diabetic retinopathy screening covered by insurance?

In most countries, including the U.S., UK, and New Zealand, diabetic retinopathy screening is covered under preventive care benefits. In the U.S., Medicare and most private insurers cover annual screenings. In New Zealand, it’s free through the public health system for enrolled diabetes patients. Always confirm coverage with your provider before your appointment.

Can I rely on my regular eye doctor for diabetic retinopathy screening?

Yes, but only if they use standardized retinal imaging and follow clinical guidelines. Not all eye exams are created equal. A routine vision check for glasses or contacts won’t detect early diabetic retinopathy. Make sure your doctor uses fundus photography and assesses for diabetic eye disease specifically. If they don’t, ask for a referral to a specialist or a dedicated diabetic eye screening program.

What if I can’t afford treatment for diabetic retinopathy?

Treatment for diabetic retinopathy, including injections and laser therapy, is often covered by insurance. In countries with public healthcare systems like New Zealand, the UK, and Canada, these treatments are free or low-cost. If you’re in a country without universal coverage, ask your clinic about financial assistance programs. Many pharmaceutical companies offer patient support for medications like Eylea or Lucentis. Never delay treatment because of cost-early intervention is far less expensive than managing vision loss.