Before 1995, if you lived in a low-income country and needed life-saving medicine like antiretroviral drugs for HIV, you had a decent chance of getting it cheaply. Generic versions were made locally using different manufacturing methods - even if the original drug was patented abroad. That changed when the TRIPS agreement came into force. Suddenly, countries couldn’t just copy drugs anymore. Patents became global, and prices shot up - sometimes by more than 200%. This isn’t theoretical. It happened in South Africa, Brazil, India, and dozens of other places where people died because they couldn’t afford treatment.

What the TRIPS Agreement Actually Does

The TRIPS Agreement is a binding international treaty under the World Trade Organization (WTO) that sets minimum standards for intellectual property protection across all 164 member countries. It was signed in 1994 as part of the Uruguay Round of trade talks and took effect on January 1, 1995. Developed by the U.S., EU, and Japan, it was designed to protect innovation - but its biggest impact has been on medicine.Here’s what TRIPS changed for drugs:

- Every country must now grant 20-year patents from the date of filing - not from when the drug hits the market.

- Process patents are no longer enough. If a drug is patented, even if you make it using a different chemical process, you’re still infringing.

- Regulatory agencies can’t approve generic versions until the patent expires - and in many places, they also can’t use the original company’s clinical trial data to speed up approval. This is called data exclusivity, and it adds 5-10 extra years of monopoly.

- There are rules for compulsory licensing - letting governments allow others to make a drug without the patent holder’s permission - but only if the country can’t make it themselves and only for its own population.

Before TRIPS, only 23 of 102 developing countries allowed product patents for medicines. By 2010, that number was 147. The shift wasn’t gradual. It was forced. Countries had to rewrite their laws, often under pressure from trade threats or aid conditions.

How Generic Medicines Got Caught in the Crossfire

Generic drugs aren’t cheap because they’re low quality. They’re cheap because they don’t pay for R&D. The original company spends $2-3 billion and 10-15 years developing a drug. Generics skip that. They just copy the formula. That’s how antiretroviral drugs dropped from $10,000 per patient per year in 2000 to $75 by 2019 - in countries that could produce or import them.But TRIPS blocked that path.

Take India. Before 2005, India only protected drug manufacturing processes, not the drugs themselves. That’s why it became the pharmacy of the developing world - making affordable HIV, hepatitis, and cancer drugs for millions. After TRIPS compliance kicked in, India had to start granting product patents. The result? Prices for cancer drugs like imatinib jumped 300-500% overnight, according to a 2008 Lancet Oncology study. People who had been getting treatment for $200 a year suddenly faced costs of $1,000 or more.

Thailand tried to use TRIPS’s own flexibilities. In 2006, it issued a compulsory license for the HIV drug efavirenz. The U.S. government responded by threatening trade sanctions. Brazil did the same with efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir. Both were pressured into backing down - not because they broke the rules, but because they dared to use them.

The Doha Declaration and the Broken Promise of Flexibility

In 2001, after years of outcry from activists, health groups, and affected governments, the WTO issued the Doha Declaration. It said: “TRIPS should not prevent countries from taking measures to protect public health.” It explicitly affirmed the right to use compulsory licensing and said countries facing public health crises could override patents.It sounded like a win.

But here’s the catch: TRIPS still said any compulsory license had to be used “predominantly for the domestic market.” That meant a country like Rwanda - with no drug factories - couldn’t import generics made in India. India could make the drug. Rwanda needed it. But the law said no cross-border trade.

So in 2005, the WTO added a “Paragraph 6 Solution.” It allowed countries without manufacturing capacity to import generics made under compulsory license. Sounds good, right?

It didn’t work.

Why? Because the process was a bureaucratic nightmare. Exporting countries had to pass special laws. Importing countries had to prove they had no capacity. The paperwork took months. The only two countries that ever used it? Canada and Rwanda. In 2007, Canada shipped 270,000 doses of antiretroviral drugs to Rwanda. That was it. By 2016, only one shipment of malaria medicine had ever moved under this rule. The system was designed to fail.

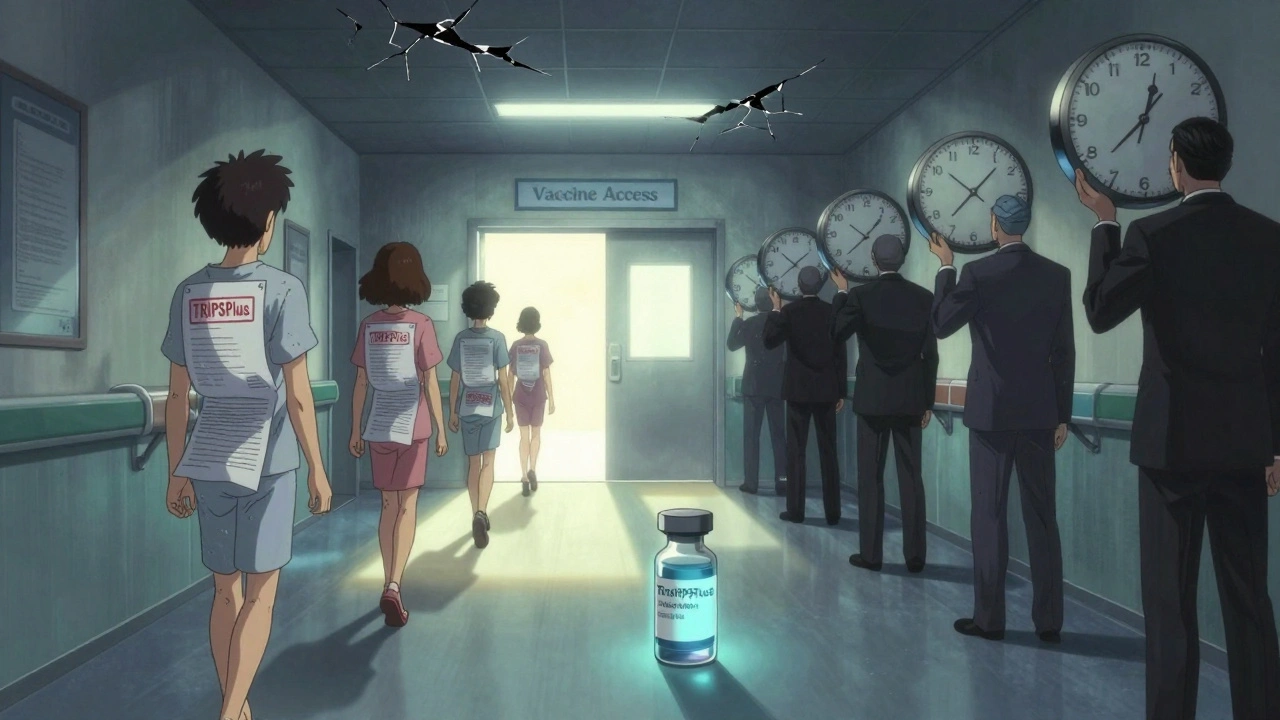

TRIPS Plus: When the Rules Get Even Tougher

The WTO didn’t stop with TRIPS. Wealthy countries pushed even stricter rules through bilateral trade deals - called TRIPS Plus. These aren’t required by international law. They’re forced through pressure.Here’s what TRIPS Plus usually includes:

- Extending patent terms beyond 20 years (e.g., for “delays” in regulatory approval)

- Adding 8-10 years of data exclusivity (far beyond TRIPS’s 5-year minimum)

- Blocking generic approval even after patent expiry - called “patent linkage”

- Restricting compulsory licensing to only extreme emergencies like war or terrorism

As of 2020, 85% of U.S. free trade agreements had these extra restrictions. The EU-Vietnam deal, signed in 2020, gave 8 years of data exclusivity. That’s longer than the original patent. It means a drug might be off-patent, but no generic can enter the market for another eight years.

And it’s spreading. Countries signing trade deals often don’t realize they’re giving up their right to make cheap medicines. The U.S. and EU use aid, investment, and market access as leverage. If you want to export textiles to the U.S., you need to agree to block generics. It’s not illegal - but it’s not fair either.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Left Behind?

The pharmaceutical industry says strong patents are necessary to fund innovation. And there’s truth to that. About 70% of new drugs since 2010 came from companies in countries with strong IP laws. But here’s the flip side:- Of the 1,223 new drugs developed between 1975 and 1997, only 13 were for tropical diseases like malaria or sleeping sickness.

- Most “innovation” isn’t for new cures - it’s for minor tweaks to existing drugs just to extend patents (called “evergreening”).

- When a drug becomes generic, prices drop by 80-95%. That’s not a market failure - it’s proof that competition works.

Meanwhile, the WHO found that countries implementing TRIPS without public health safeguards saw a 15-20% drop in generic availability within five years. In low-income countries, 80% of medicines are off-patent - but still unaffordable because of patent linkage, slow approvals, or lack of distribution.

And the cost? Real people. In South Africa, 40 pharmaceutical companies sued the government in 1998 for trying to allow generics. The case was dropped only after global protests. In Brazil, the U.S. threatened sanctions for producing generic HIV drugs - then quietly backed off when public pressure mounted.

The COVID-19 Waiver: A Glimmer of Change?

In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a temporary waiver of TRIPS protections for COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments. Over 100 countries supported it. The U.S., EU, and Switzerland blocked it for over a year.Why? Because the industry argued that waiving patents wouldn’t help - manufacturing capacity was the real bottleneck. They were partly right. But the waiver wasn’t about factories. It was about freedom. About letting countries make their own versions without fear of lawsuits. About letting India, South Africa, and Brazil produce vaccines without waiting for permission.

In June 2022, the WTO finally agreed to a limited waiver - covering only vaccines, not treatments or diagnostics. And even then, the rules were so narrow that few countries used it. It was symbolic. Not systemic.

But it showed something: the world can change TRIPS. It’s not set in stone. The Doha Declaration didn’t fix everything - but it opened the door. The COVID waiver didn’t solve access - but it proved that pressure works.

What’s Next for Generic Medicines?

The Medicines Patent Pool, created in 2010, is one of the few working alternatives. It’s a UN-backed organization that negotiates voluntary licenses with drug companies. So far, it’s secured rights for 16 HIV drugs, 6 hepatitis C drugs, and 4 TB treatments. It’s reached 17.4 million people in low- and middle-income countries.But voluntary deals are not a solution. They’re a band-aid. Companies choose what to license - and often exclude newer, more expensive drugs. They set prices. They control supply.

Real change requires two things:

- Reforming TRIPS to allow cross-border compulsory licensing without bureaucracy.

- Ending TRIPS Plus provisions in trade deals - especially data exclusivity and patent linkage.

Until then, the system remains designed to protect profits - not people. The gap between rich and poor countries in medicine access hasn’t narrowed. It’s widened. And the reason isn’t lack of science. It’s lack of political will.

Can a country still make generic drugs under TRIPS?

Yes - but it’s hard. Countries can issue compulsory licenses if they face a public health emergency, but they must first try to get a voluntary license from the patent holder. The license can’t be exported unless the country has no manufacturing capacity and follows the complex 2007 WTO procedure. Only a handful of countries have ever done this successfully.

Why do generic drugs cost so little compared to brand-name drugs?

Generic manufacturers don’t pay for the original research, clinical trials, or marketing. They only pay to replicate the formula and get regulatory approval. Since multiple companies can make the same drug once the patent expires, competition drives prices down - often by 90%. The original drug company recoups its R&D costs during the patent monopoly period.

Does TRIPS prevent all generic production?

No. TRIPS only blocks product patents - not all generic production. Countries can still make generics for drugs that aren’t patented, or for drugs where the patent has expired. But many countries now have extra rules - like data exclusivity or patent linkage - that delay generics even after patents end. These are often added through trade deals, not TRIPS itself.

What’s the difference between a patent and data exclusivity?

A patent gives the drug maker exclusive rights to make and sell the drug for 20 years. Data exclusivity means regulators can’t use the original company’s clinical trial data to approve a generic version - even after the patent expires. This can add 5-10 more years of monopoly. It’s a hidden barrier that most people don’t know about.

Why did India lose its status as the pharmacy of the developing world?

Before 2005, India only protected drug manufacturing processes, not the final product. That allowed companies to make generic versions of patented drugs using different methods. After TRIPS compliance, India had to start granting product patents. That meant it could no longer legally copy many new drugs - even if they were life-saving. Production of generics for export dropped sharply after 2005, especially for newer cancer and HIV drugs.

Final Thoughts

The TRIPS agreement didn’t just change patent law. It changed who lives and who dies. It turned medicine from a public good into a trade commodity. And while some countries found ways to fight back - through activism, legal challenges, or the Medicines Patent Pool - the system still favors corporations over patients.There’s no technical reason why a child in Malawi can’t get the same HIV drug as a child in New York. There’s only a political one. Until that changes, the fight for generic access won’t be over. It’s not about innovation. It’s about justice.