Insulin saves lives. But if it’s not used correctly, it can also put lives at risk. Every year, thousands of people end up in emergency rooms because of insulin mistakes - not because they forgot to take it, but because they took too much. Or the wrong kind. Or they used the wrong syringe. The problem isn’t laziness or carelessness. It’s confusion. And confusion kills.

Understanding Insulin Concentrations: U-100 vs. U-500

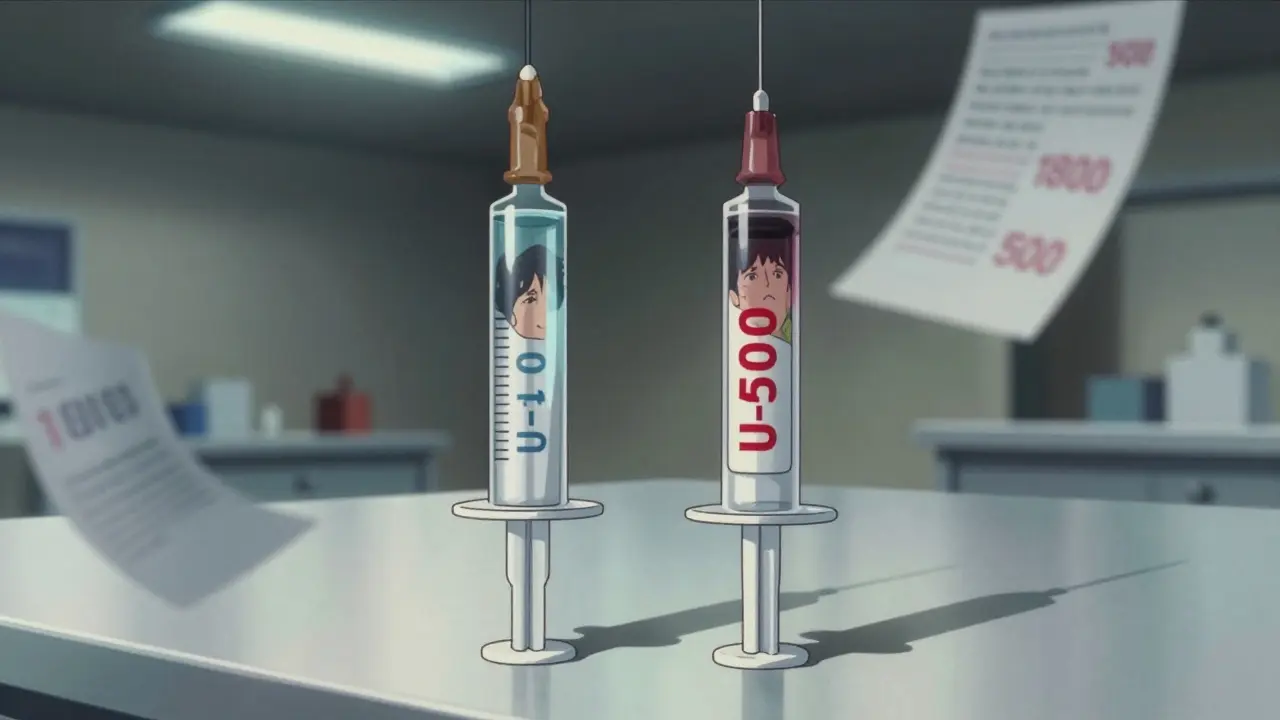

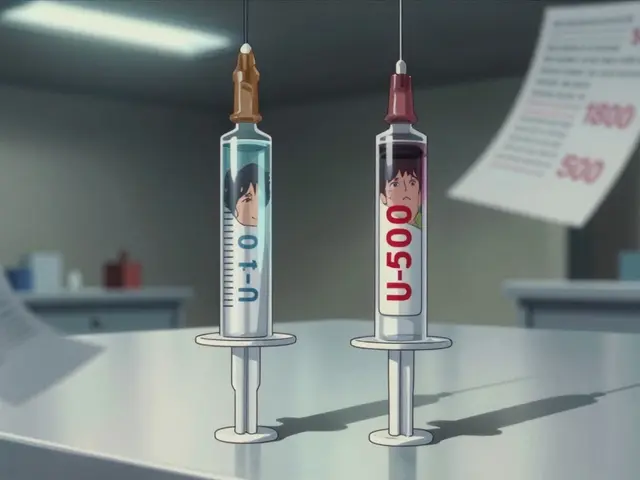

Not all insulin is the same. The most common type is U-100, meaning 100 units per milliliter. That’s what most people use. But there’s also U-500 - five times stronger. If you use a U-100 syringe to draw up U-500 insulin, you’ll give yourself five times the dose you think you’re giving. That’s not a small error. That’s a medical emergency.

U-100 insulin contains about 34.7 micrograms of insulin per unit. U-500? Each unit has roughly 36 micrograms - almost the same mass, but five times the potency. That’s why you can’t swap syringes or guess. If you’re on U-500, your doctor will give you a special syringe labeled for U-500 only. Never use a regular insulin syringe unless you’re 100% sure you’re on U-100.

Even small mix-ups can lead to severe hypoglycemia. One patient took U-500 with a U-100 syringe and dropped to 28 mg/dL. They needed ICU care. That’s not rare. It happens more often than you’d think.

The Hidden Math: Why Your Insulin Dose Might Be Wrong

Doctors and patients use rules to calculate insulin doses. The Rule of 1800. The Rule of 500. These are shortcuts. But here’s the problem: many of the calculators online, even in medical journals, use the wrong numbers.

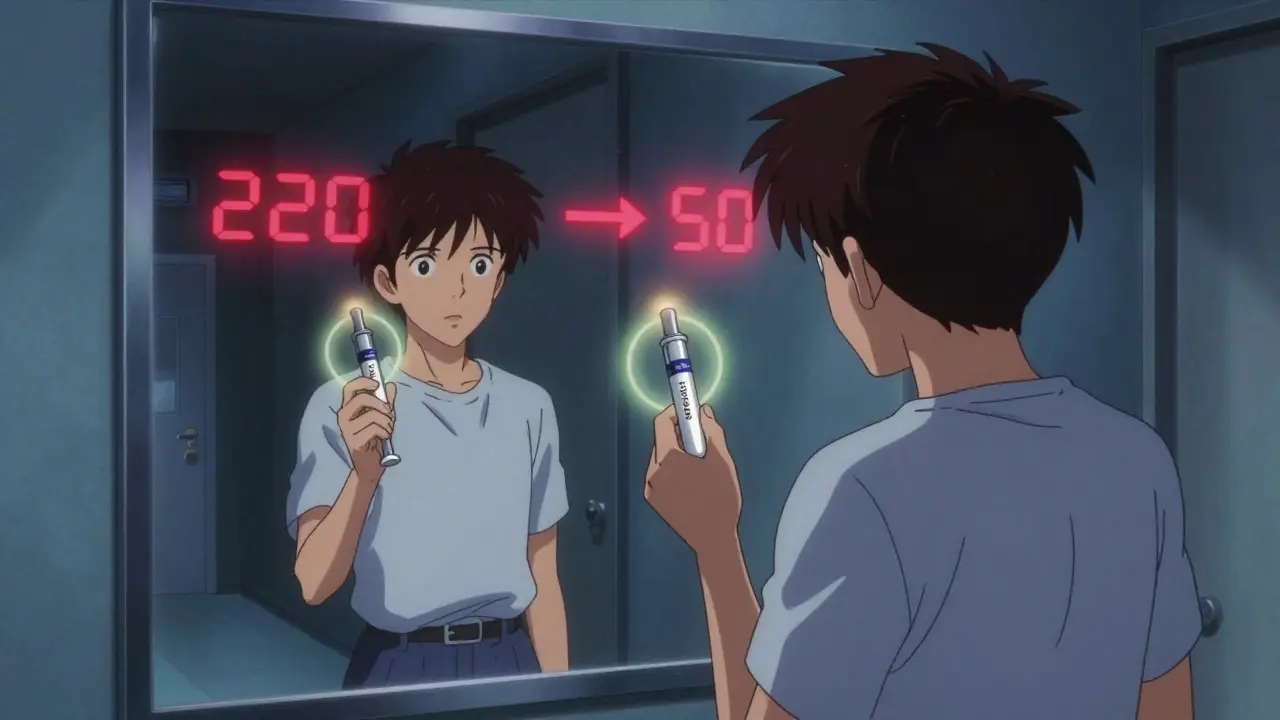

The Rule of 1800 helps you figure out how much one unit of rapid-acting insulin lowers your blood sugar. You divide 1800 by your total daily insulin dose. If you take 40 units a day, 1800 ÷ 40 = 45. So one unit drops your blood sugar by about 45 mg/dL. Simple.

But here’s where it breaks down. Some sources use 1500 instead of 1800. Others use 1700. And some online tools still use an outdated conversion factor that underreports insulin concentration by 15%. That means if you think you’re giving 10 units, you might actually be giving 11.5. That’s enough to send someone into a coma.

Why does this happen? Because insulin is measured in units (IU), which reflect biological effect - not mass. But many systems try to convert it to mass (like pmol/L). There’s only one correct conversion: 5.18. But most people use 6.0. That 15% error is built into software, textbooks, and even some hospital systems.

If you’re calculating your own doses, always double-check the numbers. Ask your diabetes educator which rule they use. Write it down. Don’t trust an app unless you know where its math comes from.

Carbohydrate Ratios and Correction Factors: How Much to Take

Mealtime insulin isn’t just about how much you eat - it’s about how sensitive your body is to insulin. That’s where the Rule of 500 comes in. You divide 500 by your total daily insulin dose to find out how many grams of carbs one unit covers.

Example: You take 50 units a day. 500 ÷ 50 = 10. So one unit covers 10 grams of carbs. If you eat a sandwich with 60 grams of carbs, you need 6 units.

But here’s the catch: that number changes from person to person. Some people need 1 unit for every 4 grams of carbs. Others need 1 unit for 30 grams. That’s why you can’t copy someone else’s ratio. Your body is unique.

Correction factor is the other half. If your blood sugar is 220 and your target is 100, that’s a 120-point difference. If your correction factor is 45 (from the Rule of 1800), you divide 120 by 45 = 2.7 units. Round to 3. So you’d take 6 units for carbs + 3 units to correct = 9 units total.

But if your correction factor is wrong - say, someone told you it was 30 instead of 45 - you’d give 4 units to correct, not 3. Now you’re overcorrecting. Blood sugar plummets. You feel shaky. You pass out. That’s hypoglycemia. And it’s preventable.

Switching Insulin Types: The Hidden Dose Trap

Switching from one insulin to another isn’t as simple as swapping bottles. NPH insulin to Lantus? You reduce the dose by 20%. Why? Because Lantus is more predictable. Giving the same dose can cause low blood sugar.

Example: You’re on 60 units of NPH daily. Switch to Lantus? Start with 48 units (60 × 0.8). Go higher and you risk hypoglycemia.

Switching from Tresiba to Basaglar? Tresiba lasts longer. If you switch to Basaglar and give the same dose once a day, you’ll overdose. The right move: split the dose. 100 units of Tresiba daily becomes 40 units of Basaglar every 12 hours. That’s 80% of your original dose, split evenly.

These aren’t suggestions. They’re clinical guidelines backed by trials. Yet, many patients are told, “Just use the same number.” That’s dangerous. Always ask: “Do I need to change the dose when switching?” Write it down. Bring the new bottle to your next appointment. Show your provider. Don’t guess.

Syringes and Pens: The Right Tool for the Right Insulin

Insulin syringes aren’t universal. A U-100 syringe holds up to 100 units in 1 mL. A U-500 syringe holds 500 units in 1 mL - but the markings are different. If you use a U-100 syringe for U-500, you’ll draw up 10 units thinking it’s 10, but it’s actually 50. That’s a 400% overdose.

Insulin pens are safer - but only if you match the pen to the insulin. Lantus pens only work with Lantus. Tresiba pens only work with Tresiba. You can’t refill a pen with a different insulin. Ever.

And never, ever share pens or syringes. Even if you clean them. Even if you think it’s “just once.” Blood can get inside. You can get infections. Or worse - you could accidentally give someone else’s insulin. One case report showed a man gave his wife his insulin pen. She was on a different dose. She went into a coma.

Use color-coded labels. Write the insulin name and dose on the pen cap. Keep your supplies in a dedicated bag. Don’t let them mix with other meds.

Hypoglycemia: The Silent Killer

Hypoglycemia - low blood sugar - is the most common and dangerous side effect of insulin. It’s not just about feeling shaky. It’s about confusion, seizures, coma, even death.

Signs: sweating, trembling, hunger, dizziness, rapid heartbeat, blurred vision, irritability, confusion. If you’re not sure, check your blood sugar. Don’t wait. If it’s below 70 mg/dL, treat it immediately.

Use the 15-15 rule: 15 grams of fast-acting carbs (4 glucose tablets, ½ cup juice, 1 tablespoon honey), wait 15 minutes, check again. If still low, repeat. Once it’s back above 70, eat a snack with protein and carbs if your next meal isn’t for more than an hour.

But prevention is better than treatment. Keep glucose tablets in your car, your purse, your desk. Tell your family and coworkers how to help. Wear a medical ID. Set phone alarms for meals and checks. Use a CGM if you can - it alerts you before you crash.

When to Call for Help

You don’t have to do this alone. If you’ve had two or more episodes of severe hypoglycemia (requiring help from someone else), it’s time to reevaluate your plan. Same if your blood sugar drops below 50 mg/dL without a clear reason.

Call your doctor if:

- You’re consistently going low after meals

- Your correction factor doesn’t seem to work

- You switched insulins and feel off

- You’re confused about your dose

Don’t wait until you’re in the ER. Talk to your diabetes educator. Ask for a dose review. Bring your logbook or app data. Show them your syringes and pens. Let them see your routine.

Final Checklist: Insulin Safety in 5 Steps

- Know your concentration: Is it U-100 or U-500? Match the syringe or pen.

- Verify your math: Use 1800 for correction, 500 for carbs. Double-check your calculator.

- Never guess a switch: When changing insulin types, always ask: “Do I reduce the dose?”

- Carry treatment: Glucose tablets, juice, or candy - always. No exceptions.

- Teach someone: Make sure a family member or friend knows how to give glucagon if you pass out.

Insulin isn’t dangerous because it’s powerful. It’s dangerous because we treat it like a simple pill. It’s not. It’s a precision tool. Get the details right, and it keeps you alive. Get them wrong, and it can end your life.

Can I use the same syringe for U-100 and U-500 insulin?

No. U-100 and U-500 insulin have different concentrations. Using a U-100 syringe with U-500 insulin means you’ll inject five times more insulin than intended. Always use the syringe labeled for your specific insulin type. U-500 requires a special syringe with different markings.

Why does my insulin dose change when I switch from NPH to Lantus?

Lantus (insulin glargine) is more predictable and lasts longer than NPH. Because of this, you typically need to reduce your dose by about 20% when switching to avoid low blood sugar. For example, if you were taking 60 units of NPH, you’d start with 48 units of Lantus. Always follow your provider’s guidance - never assume the dose stays the same.

What’s the difference between the Rule of 1800 and the Rule of 1500?

The Rule of 1800 estimates how much one unit of rapid-acting insulin lowers your blood sugar: 1800 ÷ total daily insulin dose = mg/dL drop per unit. The Rule of 1500 is outdated and used by some older sources - it overestimates insulin sensitivity. Using 1500 instead of 1800 can lead to giving too much insulin and causing hypoglycemia. Stick with 1800 unless your provider tells you otherwise.

How do I know if my insulin-to-carb ratio is correct?

Test it by eating the same amount of carbs at the same time of day, without correcting for high blood sugar. Check your blood sugar 2-3 hours after the meal. If it’s within 20 mg/dL of your target, your ratio is likely right. If it’s much higher, you need more insulin per gram. If it’s lower, you need less. Work with your diabetes educator to fine-tune this over time.

What should I do if I accidentally take too much insulin?

If you realize you took too much insulin, eat extra carbs immediately - even if your blood sugar is normal. Aim for 20-30 grams of fast-acting carbs. Check your blood sugar every 15-30 minutes for the next 4-6 hours. Don’t skip meals. Keep glucose tablets handy. If you feel confused, dizzy, or weak, call for help. If you pass out, someone must give you glucagon and call 911.

Is it safe to use insulin pens from different brands interchangeably?

No. Insulin pens are designed to work only with their matching insulin cartridges. You cannot refill a Lantus pen with Tresiba, or vice versa. Even if the liquid looks similar, the concentration and formulation are different. Using the wrong pen can lead to incorrect dosing, high or low blood sugar, and serious health risks.

Next Steps for Safer Insulin Use

Start today. Write down your insulin type, concentration, daily dose, carb ratio, and correction factor. Put it on your fridge. Share it with a family member. Download a reliable app - one that uses the Rule of 1800 and 500, not outdated values. Set reminders for meals and checks. Talk to your provider about a continuous glucose monitor if you’re not on one already.

Insulin doesn’t have to be scary. But it demands respect. Get the details right - because when it comes to insulin, small mistakes have big consequences.