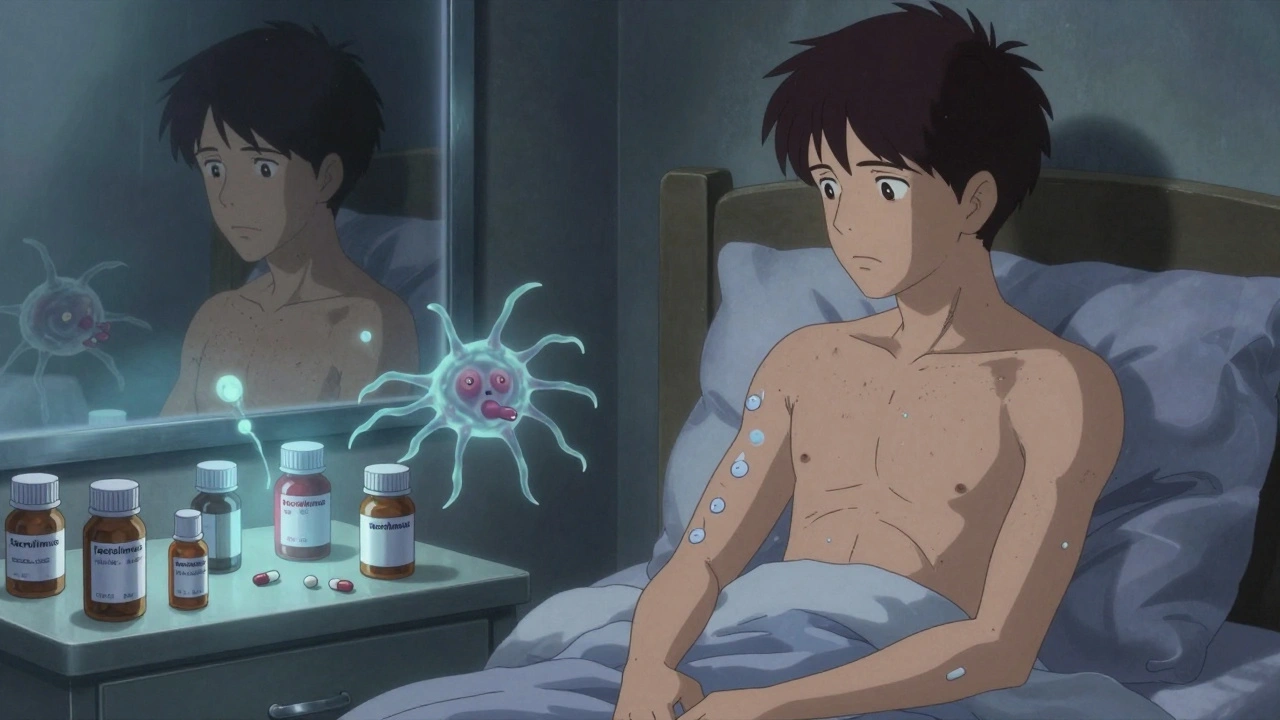

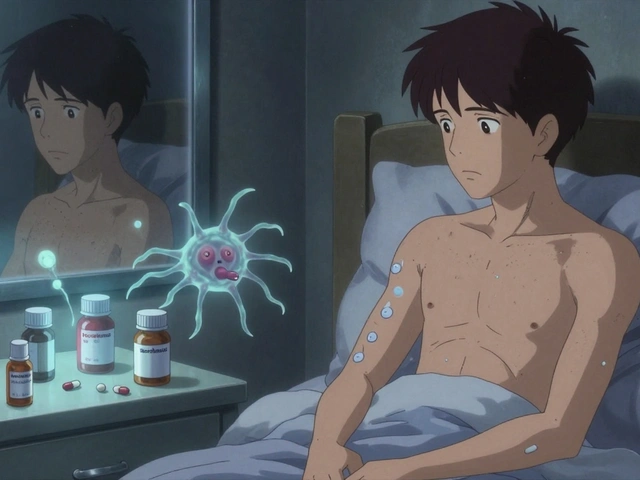

Getting a new organ is life-changing. But for most transplant recipients, the real challenge doesn’t end with surgery-it begins the moment they leave the hospital. Every day, they take a cocktail of powerful drugs designed to keep their body from rejecting the new organ. These drugs, called immunosuppressants, are essential. Without them, the immune system sees the transplanted kidney, liver, or heart as an invader and attacks it. But these same drugs weaken the body’s natural defenses, opening the door to a long list of side effects and dangerous drug interactions.

How Immunosuppressants Work-and Why They’re Necessary

Transplant recipients need to take immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives. There’s no way around it-unless you’re an identical twin, your body will never fully accept a donor organ. The goal isn’t to eliminate the immune system, but to quiet it enough to let the organ survive. The most common approach today is a triple therapy: a calcineurin inhibitor (like tacrolimus or cyclosporine), an antimetabolite (like mycophenolate or azathioprine), and a corticosteroid (like prednisone).

Tacrolimus is the most widely used calcineurin inhibitor in the U.S., prescribed to over 90% of kidney transplant patients. It works by blocking a key signal that tells T-cells to attack. Mycophenolate stops immune cells from multiplying by cutting off their DNA supply. Prednisone reduces inflammation across the whole body. Together, they keep rejection rates low. In fact, thanks to these drugs, 90% of kidney transplants still work after one year-up from barely 50% in the 1960s.

Common Side Effects: More Than Just Nausea

Side effects aren’t rare. They’re the rule. Most recipients deal with at least three ongoing issues. The most common? High blood pressure (affects 78%), high cholesterol (62%), and diabetes (35%). These aren’t just inconveniences-they increase the risk of heart disease, the leading cause of death in transplant patients after the first year.

One of the most visible side effects comes from steroids. Many patients gain 15 to 20 pounds in the first six months. Their face swells into what’s called a “moon face,” their neck develops a “buffalo hump,” and their skin thins out. One patient on Reddit described staring at herself in the mirror and not recognizing who she saw. It’s not vanity-it’s a biological change that affects self-image and mental health.

Gastrointestinal problems are also widespread. About half of people taking mycophenolate get diarrhea, nausea, or stomach pain. Azathioprine is easier on the gut but can crash white blood cell counts, making infections more likely. And then there’s fatigue-72% of recipients say they’re constantly tired, even when their labs look good. Sleep is disrupted. Mood swings are common. Some call it “steroid rage.”

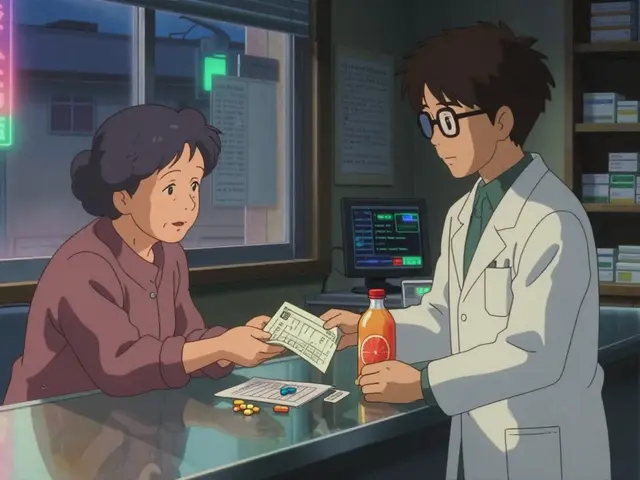

Drug Interactions: A Hidden Danger

Immunosuppressants don’t live in a vacuum. They’re metabolized by the same liver enzymes (CYP3A4) that break down hundreds of common medications. A simple change-like starting an antifungal cream for athlete’s foot-can spike tacrolimus levels by 200%. That can lead to kidney damage, tremors, seizures, or even organ failure.

On the flip side, antibiotics like rifampin can make tacrolimus useless by speeding up its breakdown. If your levels drop too low, your body starts rejecting the transplant. That’s why every new medication-even over-the-counter ones-needs to be checked by your transplant team. Garlic supplements, St. John’s wort, grapefruit juice, and even some antacids can interfere. One study found that 30-40% of commonly prescribed drugs interact with calcineurin inhibitors.

Therapeutic drug monitoring is non-negotiable. Blood tests for tacrolimus levels start twice a week after transplant, then move to weekly, biweekly, and eventually monthly. Without these checks, you’re flying blind. A level that was safe last month could be toxic this month.

Long-Term Risks: Cancer and Kidney Damage

Suppressing the immune system doesn’t just make you prone to colds-it makes you prone to cancer. Skin cancers are the most common, affecting nearly a quarter of liver transplant recipients. But it’s not just skin. Gastrointestinal cancers, lymphoma, and HPV-related cancers occur 100 times more often than in the general population. The FDA requires black box warnings on all immunosuppressants for this reason.

Kidney damage is another silent threat. Even though the new kidney is working, the drugs meant to protect it can slowly destroy it. Up to 40% of recipients show signs of chronic kidney injury five years after transplant. That’s why some patients switch from tacrolimus to sirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor that’s less toxic to the kidneys. But sirolimus brings its own problems: mouth ulcers, high triglycerides, and slower wound healing. One patient switched and saw his kidney function improve from GFR 38 to 52-but now he needs statins and deals with painful sores every week.

Quality of Life: The Hidden Cost

Surviving isn’t the same as living well. A survey of 1,247 transplant recipients found that 41% said side effects significantly lowered their quality of life. They can’t eat raw sushi because of Listeria risk. They avoid crowds during flu season. They carry hand sanitizer everywhere. They can’t travel far from their transplant center-92% of U.S. programs require patients to live within two hours for the first year.

And then there’s the mental toll. The constant fear of rejection. The guilt of taking so many pills. The frustration of being told to avoid things they used to love. One patient said, “I’m alive, but I don’t feel like me anymore.”

New Options and the Future

There’s hope on the horizon. In 2023, the FDA approved voclosporin, a new calcineurin inhibitor with fewer kidney side effects. Belatacept, a drug that blocks immune signals without harming the kidneys, has shown lower rates of heart disease and cancer in long-term studies. And in a breakthrough, researchers have achieved “operational tolerance” in 15% of kidney recipients-meaning they stopped all immunosuppressants and still kept their transplant working.

Many centers now use early steroid withdrawal, removing prednisone within two weeks for low-risk patients. This cuts steroid-related weight gain, bone loss, and diabetes risk by 35-40%. But these advances don’t eliminate the need for vigilance. Even with new drugs, patients still need regular blood tests, skin checks, and open conversations with their care team.

What You Can Do

Adherence is the biggest factor in long-term success. One study found that 22% of late graft failures were due to patients skipping doses. It’s hard to remember 8 to 12 pills a day at different times. Electronic pill dispensers that beep and send alerts have boosted adherence from 72% to 89% in some programs.

Here’s what works:

- Use a pill organizer with alarms

- Keep a written log of every medication you take, including vitamins and supplements

- Never start a new drug without checking with your transplant pharmacist

- Report any fever over 100.4°F immediately-it could be the first sign of infection

- Get annual skin checks and cancer screenings

- Stay active, eat well, and manage your blood pressure and cholesterol

The goal isn’t just to survive. It’s to live well-with as few side effects as possible. That means working closely with your team, asking questions, and never accepting “that’s just how it is” as an answer. There’s still a long way to go, but every year, the balance is shifting-toward more life, and less burden.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Stopping immunosuppressants-even if you feel great-can cause your body to reject the transplanted organ within days or weeks. Rejection can happen without warning, and once it starts, it’s often irreversible. There are rare cases where patients achieve operational tolerance and can stop meds, but this only happens under strict research protocols and is not something patients can decide on their own.

Which immunosuppressant has the least side effects?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Tacrolimus is more effective at preventing rejection but has higher risks of diabetes and tremors. Cyclosporine is less likely to cause diabetes but can damage kidneys more. Mycophenolate causes more stomach issues than azathioprine, but azathioprine lowers blood cell counts more. Sirolimus is gentler on the kidneys but causes mouth sores and high cholesterol. The best drug is the one that balances effectiveness with your personal health risks-your transplant team will tailor this for you.

Why do I need to avoid grapefruit with tacrolimus?

Grapefruit blocks the enzyme CYP3A4 in your gut and liver. This enzyme normally breaks down tacrolimus so your body can get rid of it. When grapefruit inhibits that enzyme, tacrolimus builds up to toxic levels in your blood. Even one glass of grapefruit juice can raise levels by 200%. This can cause kidney damage, nerve problems, or seizures. You need to avoid grapefruit, pomelos, Seville oranges, and related products entirely.

How often do I need blood tests after a transplant?

In the first few months, you’ll need blood tests twice a week to check tacrolimus levels and complete blood counts. After three months, it usually drops to once a week, then every two weeks, and eventually once a month. You’ll also get quarterly lipid panels, biannual glucose tests, and annual kidney function and cancer screenings. The exact schedule depends on your transplant type, how stable your levels are, and whether you’ve had any complications.

Can immunosuppressants cause weight gain?

Yes, especially corticosteroids like prednisone. They increase appetite, cause fluid retention, and change how your body stores fat. Many patients gain 15 to 20 pounds in the first six months. This isn’t just about appearance-it raises blood pressure, increases diabetes risk, and strains the heart. Some centers now use early steroid withdrawal to avoid this. Diet and exercise help, but the main fix is reducing or eliminating steroids when medically safe.

Transplant recipients live longer than ever before-but life after transplant is a daily balancing act. Every pill, every blood test, every conversation with your doctor is part of keeping the new organ alive. It’s not easy. But with the right support, knowledge, and vigilance, it’s possible to live well-with a second chance, and a stronger voice in your own care.