When you're on a TNF inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease, you're getting powerful relief from inflammation. But there's a quiet danger lurking beneath that relief: tuberculosis. Not the kind you hear about in old movies, but a reactivation of a silent, hidden infection you didn’t even know you had. This isn't theoretical. It happens. And if you're not screened properly, it can turn deadly.

Why TNF Inhibitors Put You at Risk

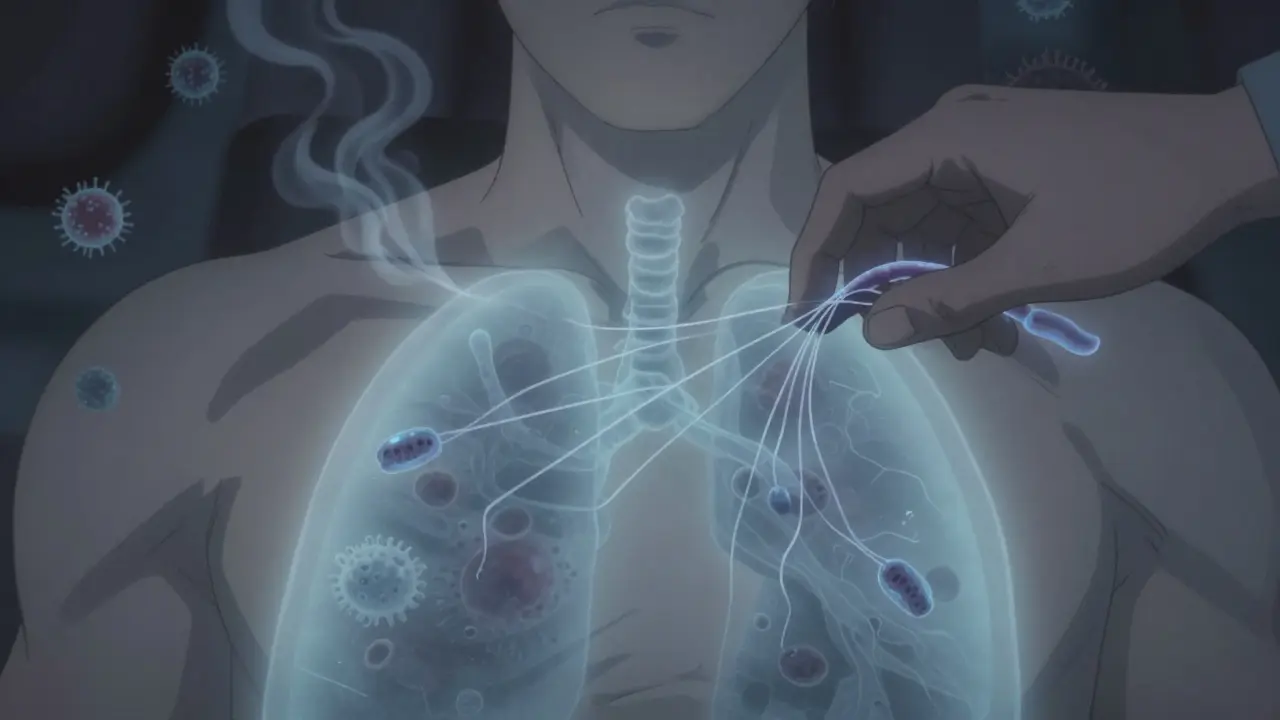

TNF-alpha is a protein your body makes to fight off infections - especially tuberculosis. It helps build and hold together granulomas, those little clusters of immune cells that trap TB bacteria and keep them from spreading. When you take a TNF inhibitor, you're blocking this protein. That’s great for reducing joint pain or skin flares. But it also leaves your body defenseless against TB that’s been sleeping in your lungs for years.

Not all TNF inhibitors are the same. There are three main types:

- Class 1 (etanercept): Works like a decoy receptor. It mostly grabs the free-floating TNF-alpha, leaving the membrane-bound version mostly untouched. This is why it carries the lowest TB risk.

- Class 2 (adalimumab): A monoclonal antibody that binds tightly to both free and membrane-bound TNF. It disrupts granulomas more thoroughly, leading to higher reactivation rates.

- Class 3 (infliximab): Similar to adalimumab, but with even stronger binding and longer tissue penetration. Studies show it has the highest risk of TB reactivation among all TNF blockers.

One study of 519 patients on TNF inhibitors found that those on adalimumab or infliximab were more than three times as likely to develop TB compared to those on etanercept. Even when 70% of patients got treatment for latent TB first, the risk didn’t drop to zero. That’s how powerful this effect is.

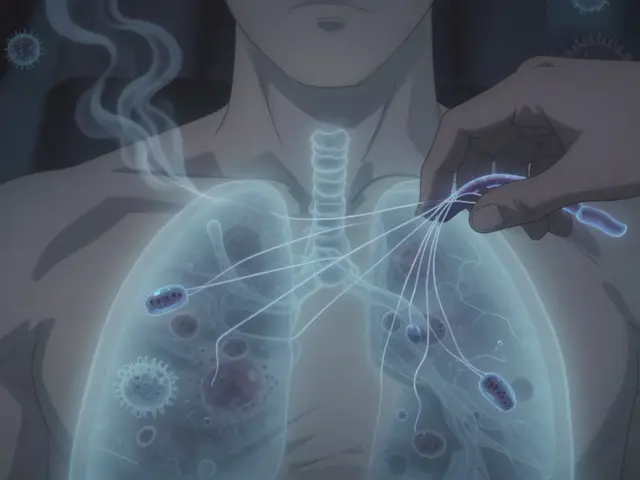

Screening: What You Need Before Starting

Before you get your first TNF inhibitor shot or infusion, you need two tests:

- Tuberculin Skin Test (TST): A small injection under the skin on your forearm. You come back in 48-72 hours to see if there’s a raised bump. It’s cheap, widely available, and used in 87% of cases.

- Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA): A blood test that’s more specific - especially useful if you’ve had the BCG vaccine (common outside the U.S.) or have had prior TB exposure. It’s used in only 6% of cases, but it’s more accurate.

Guidelines from the CDC, ATS, and IDSA say either test is fine. But if you’re from a country with high TB rates - like India, the Philippines, or parts of Africa - experts now recommend doing both. Why? Because TST can give false negatives in people with weakened immune systems, and IGRA can miss early infections.

Here’s the hard truth: 18% of patients who developed TB after starting TNF therapy had negative screening results before treatment. That means screening isn’t perfect. You can still get TB even if your test says you’re clean.

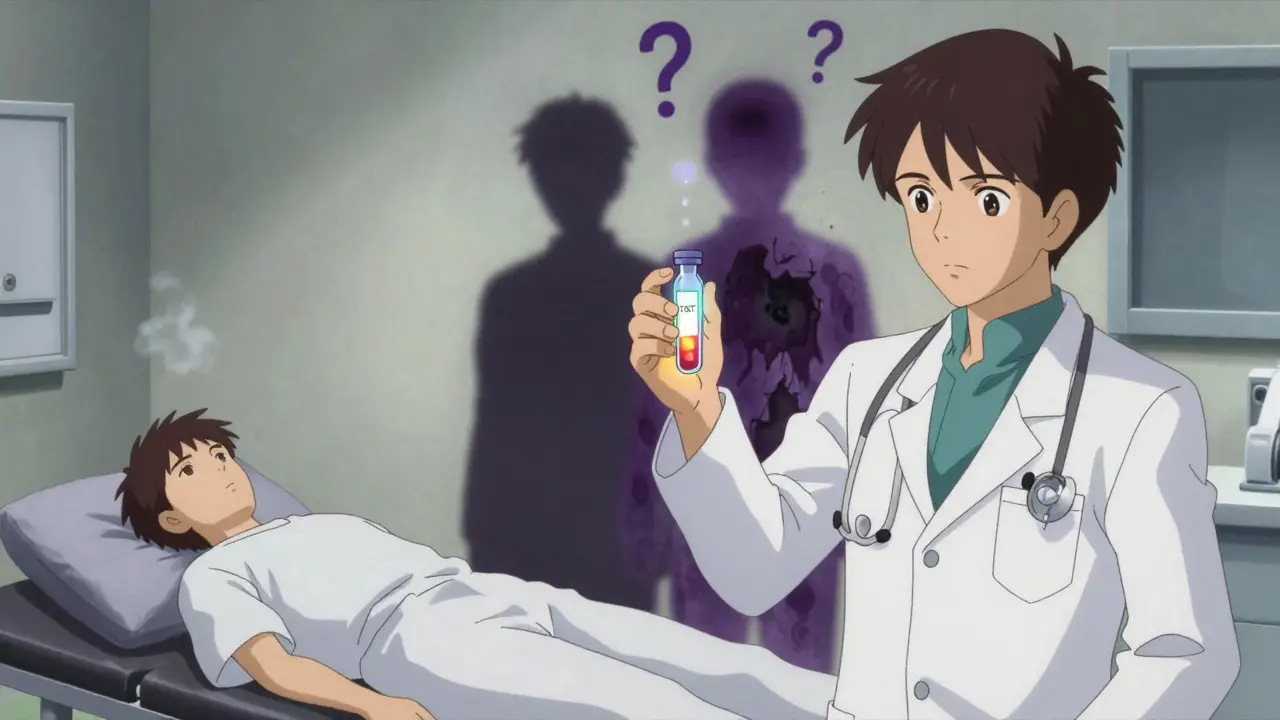

Treating Latent TB Before Starting Therapy

If either test is positive, you don’t just get your TNF inhibitor right away. You get treatment first.

The old standard was 9 months of isoniazid. But that’s tough. Many people stop because of liver toxicity, nausea, or just forgetting pills. A 2024 FDA-approved option - a 4-month combo of rifampin and isoniazid - has improved adherence from 68% to 89%. That’s huge.

Some patients get a 3-month course of rifampin alone. Others get 1 month of rifapentine and isoniazid. The goal isn’t just to kill the bacteria - it’s to kill them before your immune system gets suppressed.

And here’s something many doctors miss: if you’re from a high-TB-burden country (more than 40 cases per 100,000 per year), you should get treatment even if your tests are negative. Why? Because in places with high exposure, your risk isn’t just from old infection - it’s from recent, undetected exposure. The European League Against Rheumatism updated its guidelines in 2023 to reflect this.

Monitoring After You Start

Screening isn’t a one-time thing. TB can pop up months - even years - after you start treatment.

Most cases happen within the first 3 to 6 months. That’s why you need to be watched closely during that window. Every three months, your doctor should ask you:

- Have you had a fever that won’t go away?

- Do you wake up drenched in sweat at night?

- Have you lost weight without trying?

- Are you coughing more than usual?

These aren’t just routine questions. They’re life-saving. About 78% of TB cases in TNF inhibitor users are extrapulmonary - meaning they show up in the spine, brain, liver, or lymph nodes. That makes diagnosis harder. You might not even have a cough. You might just feel tired and have swollen glands.

And then there’s TB-IRIS - immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. It sounds scary, and it is. It happens when your immune system starts recovering after you begin TB treatment, but it overreacts. You might get a fever, swollen lymph nodes, or worsening lung inflammation. It usually shows up 45 days after starting TB drugs and 110 days after your last TNF inhibitor dose. Treatment? Often steroids for months.

Real-World Problems Doctors Face

It’s not all clear-cut in clinics. A survey of rheumatology nurses found that 27% of patients had their treatment delayed because their LTBI treatment wasn’t properly documented. Others got started on TNF inhibitors too soon - before the 30-day minimum treatment window.

And adherence is a nightmare. One provider on Sermo said: "I had a patient who took isoniazid for 2 months, then stopped because her liver enzymes went up. She didn’t tell me. Three months later, she had miliary TB."

There’s also the problem of access. In rural clinics or low-resource countries, 80% don’t have IGRA testing. They rely on TST alone. That’s risky. And in places like New Zealand - where TB is rare but not gone - doctors might underestimate the threat from patients who’ve lived in high-burden countries.

The Future: Safer Drugs on the Horizon

Researchers are working on next-generation TNF inhibitors that don’t wreck granulomas. Early animal studies show a new class - targeting CD271 instead of TNF directly - reduces TB reactivation by 80% compared to current drugs. These are in Phase II trials now. If they work in humans, they could change everything.

But until then, we’re stuck with what we have. And that means vigilance.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you’re about to start a TNF inhibitor:

- Ask for both TST and IGRA - especially if you’ve lived outside the U.S., Canada, Australia, or Western Europe.

- Confirm your LTBI treatment was completed and documented. Don’t assume your doctor knows.

- Keep track of your symptoms. Fever, night sweats, unexplained weight loss? Call your doctor immediately - don’t wait for your next appointment.

- If you’re from a high-TB-burden country, insist on treatment even if your tests are negative.

If you’ve been on a TNF inhibitor for years:

- Don’t assume you’re safe. TB can reactivate even after 2 or 3 years.

- Make sure you’re still being screened annually.

- If you travel to a high-risk country, tell your rheumatologist. You might need a repeat test.

Can I still take a TNF inhibitor if I’ve had TB before?

Yes - but only after completing full treatment for active TB and waiting at least 3 months after finishing antibiotics. You’ll also need close monitoring. Never start a TNF inhibitor while still on TB drugs.

Is TB screening covered by insurance?

In the U.S., Medicare and most private insurers cover both TST and IGRA before starting biologics. The tests usually cost $150-$300 out-of-pocket if not covered. Always check with your provider - some require pre-authorization.

Why is adalimumab riskier than etanercept?

Adalimumab binds tightly to both soluble and membrane-bound TNF-alpha. This disrupts the granulomas that keep TB contained. Etanercept mostly targets the soluble form, leaving the membrane-bound TNF - which is critical for immune control - mostly intact. That’s why etanercept has a 5-times-lower risk of TB reactivation.

What if I’m pregnant and need a TNF inhibitor?

TNF inhibitors like etanercept and adalimumab are considered relatively safe during pregnancy, but TB screening is even more critical. Latent TB can reactivate during pregnancy due to immune changes. Always screen before conception or early in pregnancy. Avoid starting therapy if you haven’t been screened.

Can I get TB from someone else while on a TNF inhibitor?

Yes. Your risk isn’t just from old infection - you can catch active TB from someone else. If you’re exposed to someone with active TB, tell your doctor immediately. You may need a repeat screening and possibly preventive treatment, even if you’ve already been screened before.

TNF inhibitors have changed lives. But they come with a silent trade-off. TB reactivation doesn’t announce itself with a bang - it creeps in quietly. The difference between catching it early and missing it could be your life. Don’t treat screening as a box to check. Treat it as your first line of defense.