When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators actually know it does? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most common way to prove that a generic drug is truly equivalent to its branded counterpart. Yet calling them the "gold standard" is misleading. They’re not perfect. They’re not always enough. And for some drugs, they might not even be the best tool we have.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

Pharmacokinetic studies track what happens to a drug inside your body after you take it. Specifically, they measure two things: how fast the drug gets into your bloodstream (Cmax), and how much of it gets there over time (AUC, or area under the curve). These aren’t abstract numbers-they’re direct reflections of how well your body absorbs the drug. If a generic drug delivers the same Cmax and AUC as the original, regulators assume it will have the same effect.

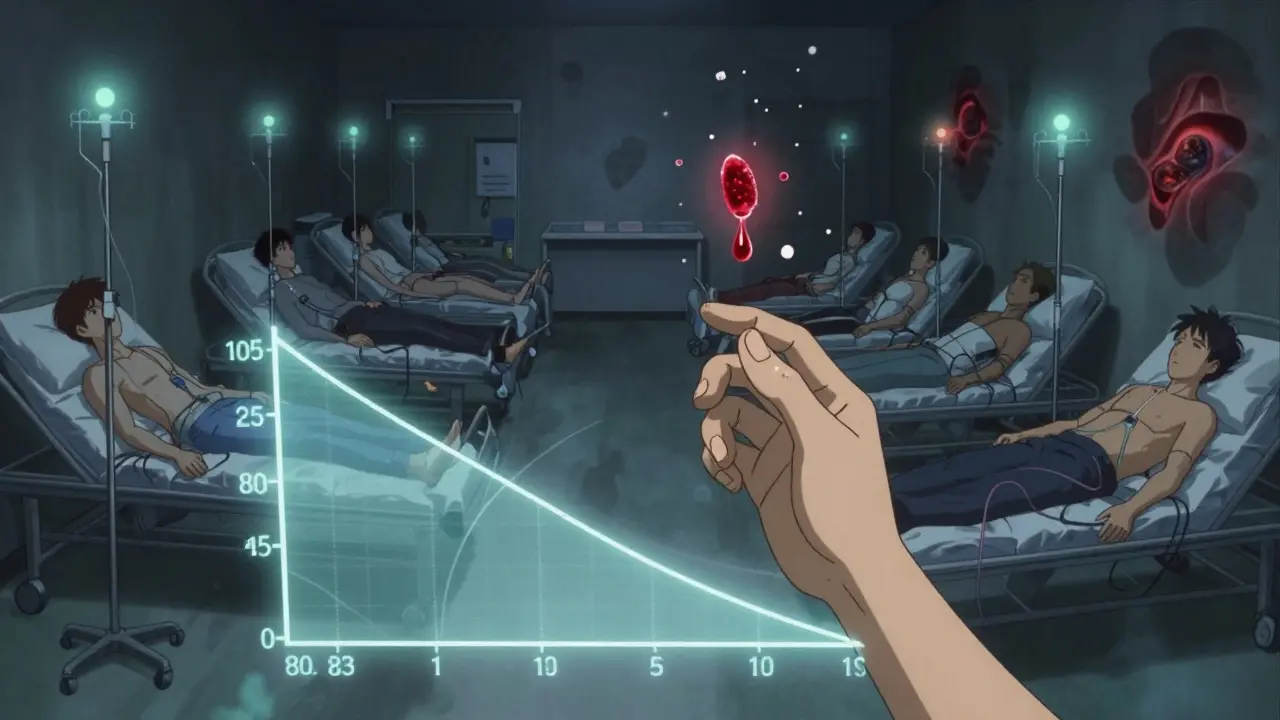

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand-name drug values for both Cmax and AUC must fall between 80% and 125%. That means the generic can’t be more than 20% weaker or 25% stronger than the original. For most drugs, this range is wide enough to account for normal biological variation between people. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, digoxin, or phenytoin-this window is too loose. So regulators tighten it to 90-111%. One percent too high? It could cause a stroke. One percent too low? It could trigger a seizure.

How These Studies Are Done

A typical bioequivalence study involves 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They’re randomly assigned to take either the brand-name drug or the generic first, then switch after a washout period. This crossover design helps cancel out individual differences in metabolism. Studies are usually done under fasting conditions, but if the drug’s absorption is affected by food-like certain antibiotics or cholesterol meds-they also test it with a meal.

The data is analyzed using statistical methods like ANOVA. The goal isn’t to prove the drugs are identical-it’s to prove they’re similar enough that no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness is expected. The FDA has approved over 95% of generic applications using this method. That’s a high success rate, but it doesn’t mean every approved generic is perfect.

When Pharmacokinetic Studies Fall Short

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: identical pharmacokinetic profiles don’t always mean identical outcomes. A 2010 study in PLOS ONE found that two generic versions of gentamicin-one made by a well-known company, the other by a lesser-known one-had the same in vitro results, the same active ingredient, and the same absorption profile. Yet one caused significantly more kidney toxicity in patients. Why? Because the excipients (inactive ingredients) affected how the drug interacted with tissues, even if plasma levels looked fine.

And that’s not an outlier. For topical creams, inhalers, nasal sprays, and injectables, measuring blood levels often tells you nothing. You can’t measure how much of a cream actually gets into the skin. You can’t track how much of an inhaler reaches deep into the lungs. For these products, pharmacokinetic studies are useless. That’s why regulators now rely on other tools: in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) for creams, or in vivo clinical endpoint studies for inhalers. One 2014 study showed IVPT using human skin samples was more accurate than even clinical trials for topical products.

The Hidden Cost and Complexity

Running a bioequivalence study isn’t cheap. It costs between $300,000 and $1 million. It takes 12 to 18 months. And it’s not just about running tests-it’s about designing the right formulation. A tiny change in the binder, coating, or particle size can alter how the drug dissolves. A generic manufacturer might spend years tweaking a formula just to hit that 80-125% window. And even then, it’s not guaranteed. The FDA has over 1,857 product-specific guidances for bioequivalence, each tailored to a different drug. One size does not fit all.

That’s why some companies now use the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). If a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable (BCS Class I), and the formulation is similar, regulators may waive the human study entirely. But this only applies to about 15% of drugs. For the rest, the old-school pharmacokinetic study remains the default.

What’s Changing in the Field

The future of bioequivalence isn’t just blood samples and IV drips. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is gaining traction. These are computer simulations that predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, organ function, and absorption patterns. Since 2020, the FDA has accepted PBPK models to waive bioequivalence studies for certain BCS Class I drugs. It’s faster, cheaper, and avoids exposing healthy volunteers to drugs unnecessarily.

For topical drugs, dermatopharmacokinetic methods (DMD) are replacing clinical trials. One 2019 study showed DMD could detect differences between formulations with over 90% accuracy-something traditional blood tests couldn’t do. And in vitro dissolution testing is becoming more sophisticated. Instead of just checking if two pills dissolve at the same rate, labs now use advanced models that mimic the stomach’s pH, enzymes, and movement.

Global Differences Matter

Not all countries play by the same rules. The FDA and EMA (European Medicines Agency) often have conflicting standards. The EMA uses a more rigid, one-size-fits-all approach. The FDA adapts its guidelines drug by drug. This creates headaches for manufacturers trying to sell generics worldwide. A product approved in the U.S. might fail in Europe because of a slightly different statistical threshold or a missing fed study. The WHO tries to harmonize standards, but only about 50 countries fully follow their guidelines. In emerging markets, enforcement is patchy, and substandard generics still slip through.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Just About Science

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $1 trillion every decade. They make life-saving treatments affordable. But the system depends on trust. If we assume pharmacokinetic studies are foolproof, we risk overlooking real risks. The FDA’s own data shows that even with identical bioequivalence results, some generics still cause unexpected side effects. That’s why ongoing post-market surveillance is critical. When a patient reports a problem, regulators dig deeper-not just into the original study, but into manufacturing, excipients, and real-world outcomes.

Pharmacokinetic studies aren’t the gold standard. They’re the most practical, widely accepted tool we have-for now. But the field is evolving. We’re moving toward a future where bioequivalence is judged not just by blood levels, but by real clinical outcomes, advanced modeling, and better testing for complex products. The goal isn’t to prove drugs are identical. It’s to prove they’re interchangeable without risk. And that’s a higher bar than a single number in a 90% confidence interval.

Are pharmacokinetic studies always required for generic drugs?

No. For certain drugs-especially those classified as BCS Class I (high solubility, high permeability)-regulators like the FDA may waive the human study if the formulation is similar and dissolution profiles match. In vitro testing and PBPK modeling are increasingly accepted as alternatives. But for most oral drugs, especially those with complex release profiles or narrow therapeutic windows, pharmacokinetic studies remain mandatory.

Why do some generic drugs cause different side effects than the brand name?

Even if two drugs have identical active ingredients and similar blood levels, differences in inactive ingredients (excipients) can affect how the drug is absorbed, metabolized, or even how it interacts with tissues. For example, a coating that dissolves too slowly in the gut might delay absorption, or a stabilizer might trigger an immune response in sensitive patients. These subtle differences aren’t always caught in standard bioequivalence studies, which focus only on plasma concentration.

Can a generic drug be approved without any human testing?

Yes, but only in rare cases. The FDA allows waivers for certain BCS Class I drugs if dissolution testing shows near-identical release profiles and the drug has a well-established safety profile. PBPK modeling is also being used to support waivers. However, this is not allowed for drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, injectables, topicals, or any formulation where absorption is unpredictable.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means two drugs have similar absorption profiles (Cmax and AUC). Therapeutic equivalence means they can be safely swapped without affecting patient outcomes. Bioequivalence is a prerequisite, but not a guarantee. Two drugs can be bioequivalent but not therapeutically equivalent if, for example, one causes more side effects due to excipients or if it’s a drug where local tissue effects matter more than blood levels-like asthma inhalers or topical steroids.

Do all countries use the same bioequivalence standards?

No. The FDA, EMA, and WHO have different guidelines. The FDA uses product-specific guidance and allows flexibility. The EMA uses a more rigid approach. Some countries accept in vitro data alone; others demand full human studies. This creates challenges for manufacturers trying to sell globally. Emerging markets often lack the resources for rigorous testing, leading to inconsistent quality.