Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, or PSC, isn’t something most people have heard of-until it hits them or someone they love. It’s a rare, slow-burning disease that quietly destroys the bile ducts inside and outside the liver. No one knows exactly why it happens, but once it starts, it doesn’t stop. There’s no cure. And for many, the only real solution is a liver transplant.

What Happens When Your Bile Ducts Scar

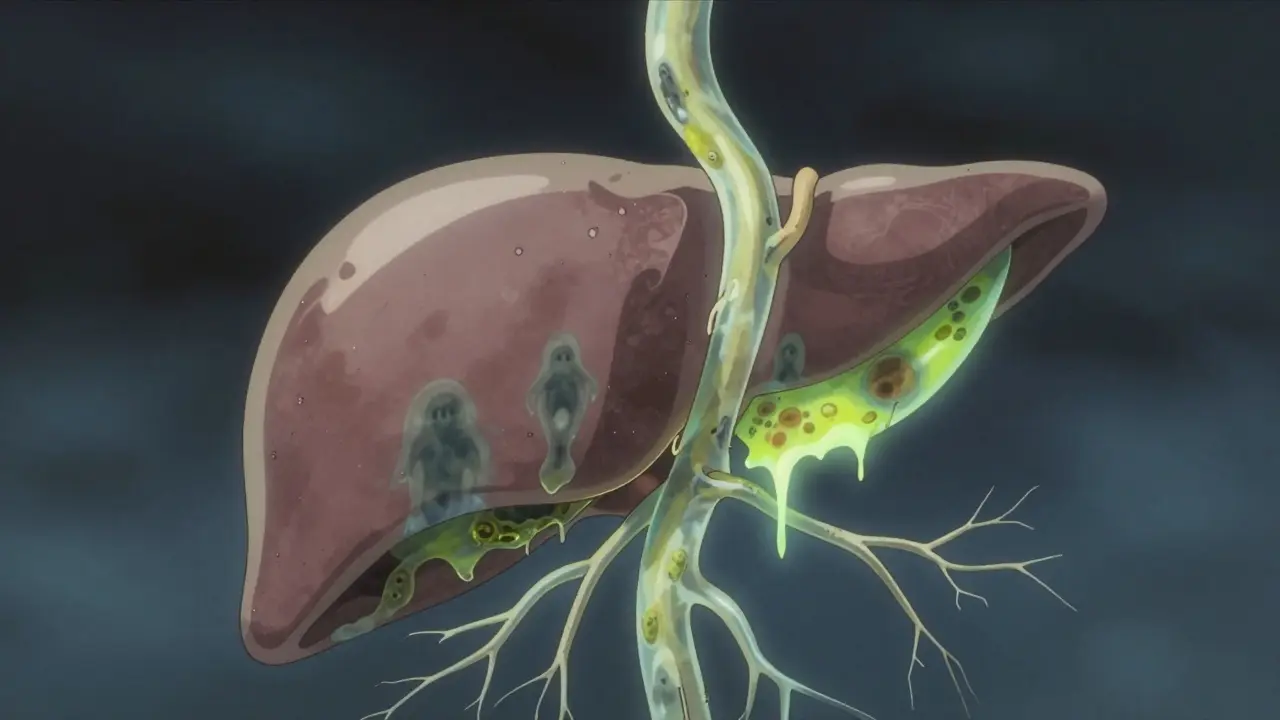

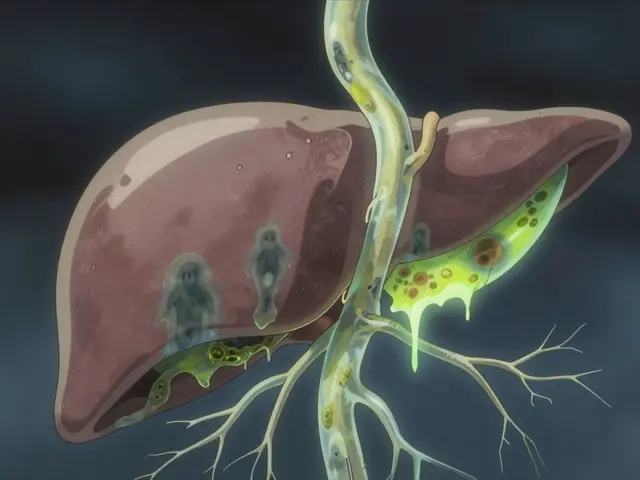

Your liver makes bile to help digest fat. That bile travels through thin tubes called bile ducts to your small intestine. In PSC, those ducts get inflamed, scarred, and narrowed-sometimes down to less than 1.5 millimeters wide. Normal ducts are 3 to 8 millimeters. When they close off, bile backs up in the liver. That’s called cholestasis. Over time, the liver gets damaged, then fibrotic, then cirrhotic. It’s a four-stage process: inflammation → scarring around ducts → bridges of scar tissue connecting areas → full-blown cirrhosis. This can take 12 to 15 years from first symptoms, but some people move faster.Unlike Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC), which attacks tiny ducts inside the liver and shows clear antibody markers, PSC is messier. It hits both big and small ducts. Only about half of PSC patients test positive for p-ANCA, a weak immune signal. And unlike PBC, there’s no single blood test that confirms it. Diagnosis usually comes from an MRCP-a special MRI of the bile ducts-or sometimes an ERCP, where a scope is inserted to take pictures. The scarring looks like a tree with broken branches: uneven, knotted, and narrowed.

Who Gets PSC-and Why

PSC doesn’t pick randomly. It’s mostly men. About two out of every three diagnosed are male. Most are between 30 and 50, with the average age at diagnosis being 40. It’s far more common in people of Northern European descent. In Sweden, it affects 6.3 per 100,000 people. Globally, it’s rare-about 1 in 100,000.But the biggest clue? Inflammatory bowel disease. Up to 80% of PSC patients also have ulcerative colitis. Some even have Crohn’s. The gut and liver are connected in ways we’re only beginning to understand. Researchers now call it the gut-liver axis. Something in the gut-maybe bad bacteria, or a leaky barrier-triggers an immune response that attacks the bile ducts in people with certain genes. The strongest genetic link? HLA-B*08:01. People with this gene are over twice as likely to develop PSC.

It’s not inherited like cystic fibrosis. But if you have a close relative with PSC, your risk goes up. And it’s not caused by alcohol, drugs, or diet. It’s autoimmune-but not in the classic sense. No one knows what flips the switch. Environmental triggers? Maybe. Viral infections? Possibly. But no smoking gun.

What It Feels Like: Symptoms No One Talks About

Many people with PSC feel fine for years. That’s why diagnosis is often delayed-by 2 to 5 years, according to patient surveys. By then, damage is already done.The most common symptoms? Fatigue. It’s not just tired. It’s bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. Then there’s itching-pruritus. Not a rash. Not dry skin. A deep, crawling, burning itch that starts inside and radiates outward. One patient on Reddit described it as "coming from my bones," especially at night. It’s so bad that some can’t sleep, can’t focus, can’t work.

Others have pain in the upper right abdomen, yellowing skin (jaundice), or dark urine. Fever and chills mean an infection in the bile ducts-acute cholangitis. That’s an emergency. Untreated, it can kill.

And here’s the silent killer: vitamin deficiencies. Because bile isn’t flowing, your body can’t absorb fat-soluble vitamins-A, D, E, K. Low vitamin D means weak bones. Low vitamin K means you bruise easily or bleed too much. These aren’t just side effects-they’re direct results of the disease. That’s why quarterly blood tests for vitamins are non-negotiable.

What Doctors Can-and Can’t-Do

There’s no pill that stops PSC. That’s the hard truth. For years, doctors gave patients high doses of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), thinking it would help. But multiple trials showed it doesn’t improve survival. In fact, doses above 28 mg/kg/day might increase the risk of serious problems. The European Association for the Study of the Liver now says: don’t use it routinely.So what’s left? Symptom control. For itching, doctors try rifampicin (an antibiotic that also reduces itch signals), naltrexone (a low-dose opioid blocker), or colesevelam (a bile acid binder). Each works for about half the people who try it. Finding the right one is trial and error.

For bone loss from low vitamin D, calcium and vitamin D supplements are standard. Colon cancer screening is critical too. Because PSC and ulcerative colitis together raise colorectal cancer risk to 10-15% over a lifetime, colonoscopies every 1-2 years are required. Many patients don’t realize this until it’s too late.

And then there’s the liver transplant. It’s the only cure. About 80% of people who get one survive at least five years. But it’s not a fix-all. PSC can come back in the new liver-rarely, but it happens. And not everyone qualifies. You have to be sick enough to need it, but healthy enough to survive surgery. Waiting lists are long. And even after transplant, you’ll need lifelong immunosuppressants.

Where Hope Is Growing

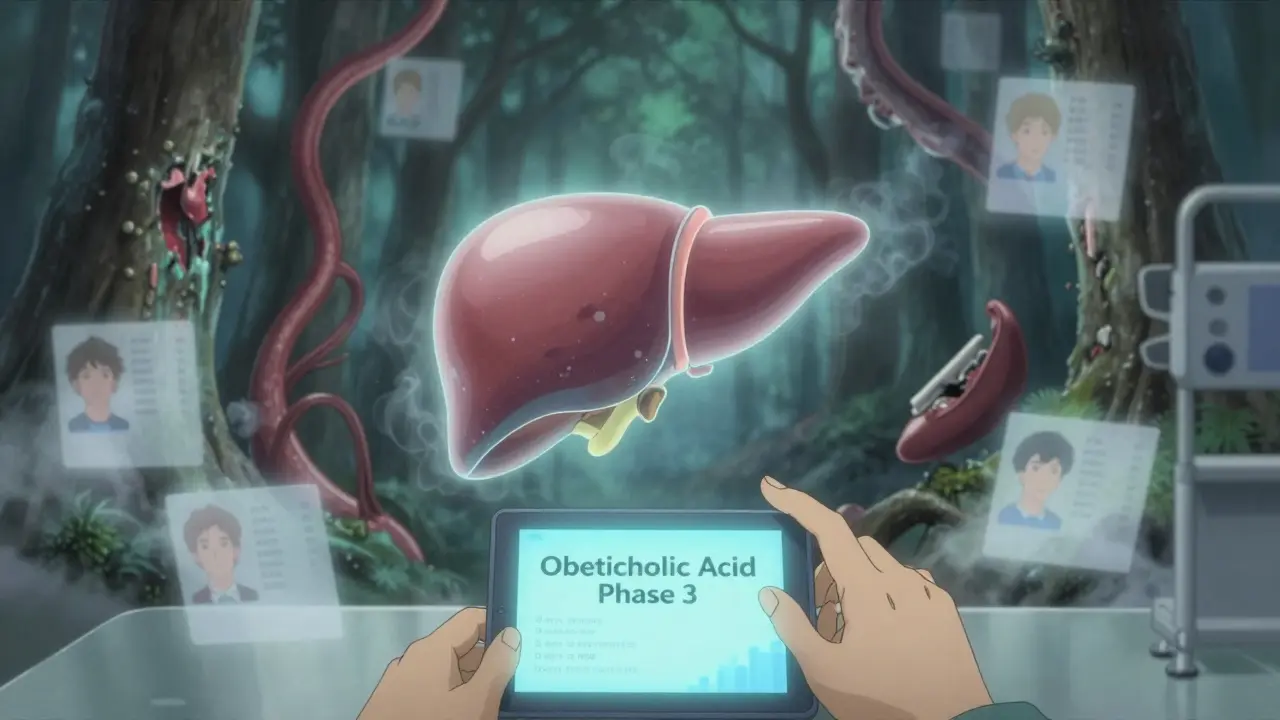

There’s real momentum in research. Five years ago, there were almost no drugs in trials for PSC. Now, there are over a dozen. One of the most promising is obeticholic acid, which targets the FXR receptor to reduce bile buildup. In a phase 3 trial, it lowered liver enzymes by 32% in 18 months. The FDA hasn’t approved it yet-safety concerns remain-but it’s close.Another drug, cilofexor, showed a 41% drop in ALP (a key liver enzyme) in early trials. It’s already been granted orphan drug status in Europe. Fibrates, usually used for cholesterol, are also showing promise in reducing bile duct inflammation.

And patient registries are making a difference. The PSC Partners Seeking a Cure registry has over 3,100 people from 12 countries. That kind of data helps researchers spot patterns, design better trials, and find who responds to what. For a disease this rare, that’s huge.

Experts predict that within five years, we’ll have at least two new drugs that actually slow or stop PSC progression-not just manage symptoms. That’s the goal. Not just a transplant. A real treatment.

Living With PSC: What You Need to Know

If you’ve been diagnosed, here’s what you must do:- See a specialist. PSC care is not general hepatology. Go to a center that sees at least 50 PSC patients a year. Patients at these centers report 85% better symptom control.

- Get an MRCP every year. It tracks duct changes better than blood tests.

- Test liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP) quarterly.

- Check vitamins A, D, E, K every three months.

- Have a colonoscopy every 1-2 years if you have ulcerative colitis.

- Know the signs of cholangitis: fever above 38.5°C, right-sided pain, jaundice. Go to the ER immediately.

- Join a patient community. You’re not alone. Over 1,200 people in one survey said they waited years for answers. You’ll find others who get it.

Most importantly-don’t wait. Even if you feel fine, the disease is still moving. The earlier you’re monitored, the better your chances of catching complications before they’re life-threatening.

Why This Disease Is Overlooked

PSC gets less than 6% of the research funding that NAFLD gets-even though it’s more likely to lead to liver cancer. The NIH spent $8.2 million on PSC research in 2022. For NAFLD? $142 million. That’s not a mistake. It’s a gap. And it’s why patients feel forgotten.Only 65% of major U.S. academic centers follow the latest international guidelines. In rural Europe, only 35% of patients live within 100 miles of a PSC specialist. Access to care isn’t equal. And that’s deadly.

But change is coming. More centers are adopting standardized care. More patients are speaking up. More researchers are listening. And with new drugs on the horizon, the next decade could be the first time in history that PSC patients have real hope beyond transplantation.

Is Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis the same as Primary Biliary Cholangitis?

No. PSC and PBC are different diseases. PSC affects both large and small bile ducts inside and outside the liver, while PBC mainly attacks the small ducts inside the liver. PBC often shows anti-mitochondrial antibodies in over 90% of cases; PSC rarely does. PSC is more common in men and linked to inflammatory bowel disease, while PBC mostly affects middle-aged women. The treatments and long-term risks also differ.

Can you live a normal life with PSC?

Yes-but it requires active management. Many people with PSC work, raise families, and travel. But fatigue and itching can be disabling. Regular monitoring, vitamin supplements, and avoiding alcohol are essential. You’ll need to see specialists often and stay on top of screenings. It’s not easy, but with good care, many live for decades without needing a transplant.

Does PSC increase the risk of liver cancer?

Yes. People with PSC have a 1.5% annual risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma, a bile duct cancer. That means over 15% of patients will develop it over 10 years. This cancer is aggressive and hard to catch early. That’s why annual MRCP scans and tumor marker tests (like CA 19-9) are critical. Some centers also do ultrasound surveillance every six months.

Why is there no cure for PSC yet?

PSC is rare, complex, and poorly understood. It doesn’t have clear immune markers like other autoimmune diseases, making drug development harder. Research funding has been minimal compared to more common liver diseases. Until recently, there were no good animal models to test treatments. Now, with patient registries and new genetic insights, scientists are making progress-but it takes time.

Can diet or supplements help with PSC?

Diet won’t cure PSC, but it can help manage symptoms. A low-fat diet may reduce digestive discomfort. Fat-soluble vitamin supplements (A, D, E, K) are essential. Some patients report less itching with probiotics or omega-3s, but there’s no strong evidence yet. Avoid alcohol completely. And never take herbal supplements without talking to your doctor-some can damage the liver.

What’s the survival rate for PSC without a transplant?

It varies. People diagnosed without symptoms have a 77% chance of surviving 10 years without a transplant. Those with symptoms at diagnosis drop to 51%. Once cirrhosis develops, survival drops further. The biggest threat isn’t liver failure-it’s cholangiocarcinoma, which reduces 5-year survival to just 10-30% if not caught early. Regular monitoring improves outcomes.